[This is a Guest Diary by Draden Barwick, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu Bachelor's Degree in Applied Cybersecurity (BACS) program [1].]

DShield Honeypots are constantly exposed to the internet and inundated with exploit traffic, login attempts, and other malicious activity. Analyzing the logged password attempts can help identify what attackers are targeting. To go through these passwords, I have created a tool that leverages HaveIBeenPwned’s (HIBP’s) API to flag passwords that haven’t appeared in any breaches.

Purpose

Identifying passwords that haven’t been seen in known breaches is useful because it can indicate additional planning and help identify patterns in these less common passwords. Anyone that operates a honeypot (and receives a lot of data on attempted use of passwords in plaintext) could benefit from this project as an additional starting point for investigations.

Development

HaveIBeenPwned maintains a large database of breached passwords and offers an API to tell if a given password has been compromised. This is done by making a request to “https://api.pwnedpasswords.com/range/#####”. Where the “#####” part in a request is the first 5 characters (prefix) of the SHA1 hash of the tested password. The site will return a list of the last 35 characters (suffix) for any password hash in the database that starts with the provided prefix. Each entry includes a count of how many times the corresponding password has been seen in breaches. This prevents anyone from knowing the full hash of the password we are looking for based on the request alone. While this consideration is not important for our use with the DShield honeypots (as all passwords seen are publicly uploaded), it is important to understand because HIBP does not allow for searching with the full hash directly [2].

To gather a list of all passwords my honeypot has gathered, I used JQ to parse the cowrie.json files located in the /srv/cowrie/var/log/cowrie directory. This command matches on any login failures or successes, and returns the password field from matching entries:

jq -r 'select(.eventid=="cowrie.login.failed" or .eventid=="cowrie.login.success") | [.password] | @tsv' /srv/cowrie/var/log/cowrie/cowrie.json*

To extend this, we can remove duplicates using sort and uniq and save the unique passwords to a file:

jq -r 'select(.eventid=="cowrie.login.failed" or .eventid=="cowrie.login.success") | [.password] | @tsv' /srv/cowrie/var/log/cowrie/cowrie.json* | sort | uniq > ~/uniquepass.txt

As of writing, this took the number of passwords from 51,601 to 16,210 unique passwords.

Now that we have a list of unique passwords, the next steps are to: read the created password file, take the SHA1 hash of each line, query the API for the hash prefix, and check for the hash suffix in the results.

To accomplish this, I created a Python script that utilizes one input file and two output files. The input file has a list of passwords to check with one entry per line. One output file stores all passwords that have been checked, the SHA1 hash, and how many times HIBP has seen the password (this file is a CSV used to avoid checking a password in the input file if it has been checked before). The other output file stores the plaintext of any password never seen by HIBP. The command line usage looks like this:

python3 queryHIBP.py uniquepass.txt passwordResults.csv unseenPasswords.txt

This resulted in the identification of 1,196 passwords that HIBP has not seen.

Code Breakdown

The code, available on GitHub [3], has thorough commenting but we will examine some parts here to gain a deeper understanding of how it functions.

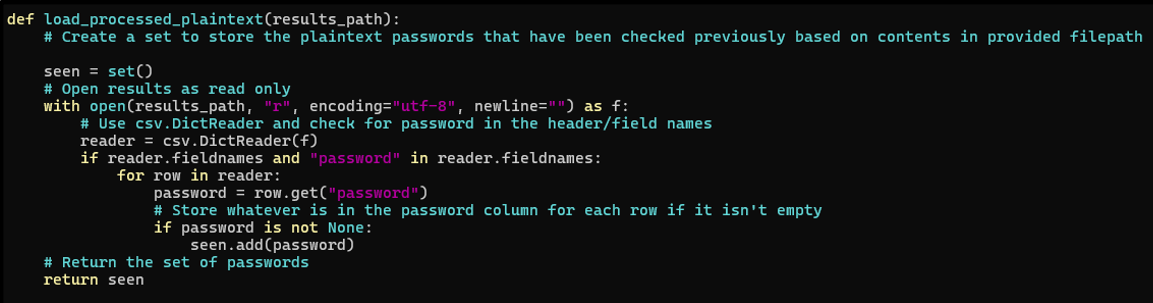

In Figure 1, we can see the section of code that handles reading the results file that includes all passwords we have searched for. This is expected to be formatted as a CSV file with a header of “password,sha1,count”. As explained above, this helps avoid checking passwords unnecessarily.

The code opens the file with csv.DictReader, checks for “password” in the header, then uses a for loop to go through all of the rows to pull non-empty passwords and add them to a set. The set is returned at the end of the function.

Figure 1: Code used to read all previously checked passwords.

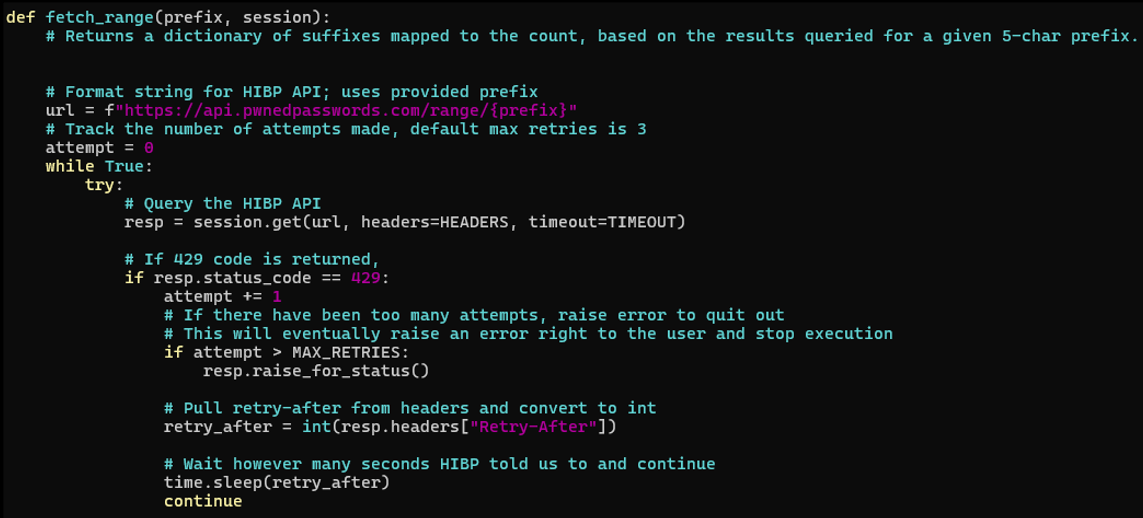

In Figure 2, we can see the code used to make API requests and handle a common error. First, a loop is established and the API request is made. Second, we check for a 429 response code which means there were too many requests. If there was a 429 error, HIBP will add a “Retry-After” header which lets us know how long to wait before trying again. The user agent is specified elsewhere as “PasswordCheckingProject” because HIBP states that “A missing user agent will result in an HTTP 403 response” [4].

Figure 2: Code used to make API requests and handle expected 429 errors.

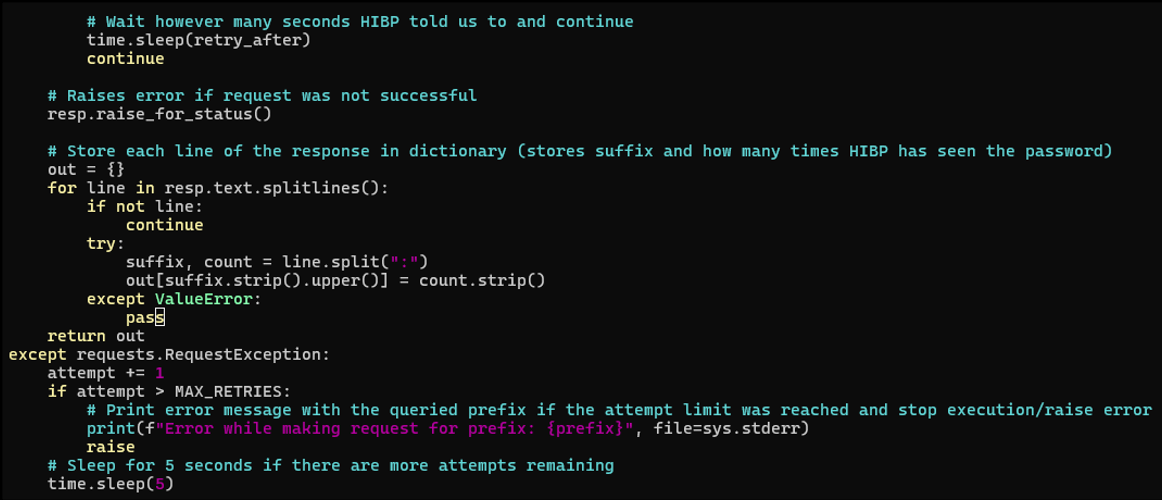

Figure 3 shows the behavior for handling additional errors and normal function. Firstly, “resp.raise_for_status” is called which would raise an exception if there were an error with the HTTP request. If there’s no error, we simply iterate through all lines of the response to save the hash suffix and count in a dictionary, then return it. If an exception is raised, we increment an “attempt” variable which lets us cap the number of retries which is set to three by default. If the max is hit here, the code will print an error message indicating what prefix was being checked and exit. If there are more retries remaining, the script will wait 5 seconds before continuing. Figure 2 has a similar check for max retries to avoid a potential infinite loop of 429 errors.

Figure 3: Code used to store & return request results or deal with continued/unexpected errors.

Implementation

To download the project and try it out with some test data, one can run the following:

git clone https://github.com/MeepStryker/queryHIBP.git

cd queryHIBP

python3 queryHIBP.py ./sampleInput.txt ./passwordResults.csv ./unseenPasswords.txt

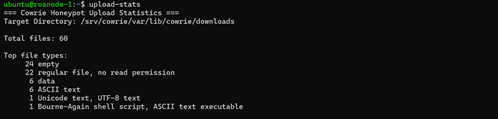

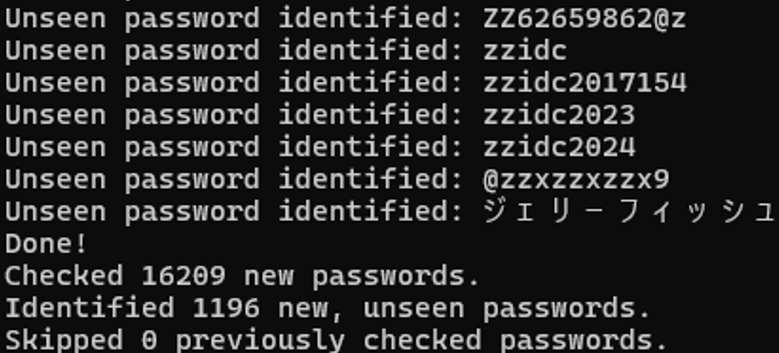

As the script runs, it will print out each unseen password identified and a short summary at the end as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Script output using real data.

Automation

To automate the use of this tool, I created a cron job to run the JQ command & output results to a file and made another job to run the script with the needed arguments. These are set to run daily with the script running 5 minutes after the JQ command. This uses the following crontab entries:

0 17 * * * jq -r 'select(.eventid=="cowrie.login.failed" or .eventid=="cowrie.login.success") | [.password] | @tsv' /srv/cowrie/var/log/cowrie/cowrie.json* | sort | uniq > ~/uniquepass.txt

5 17 * * * python3 ~/queryHIBP.py ~/uniquepass.txt ~/passwordResults.csv ~/unseenPasswords.txt

The script runs 5 minutes after the JQ command to ensure there is more than enough time to create the input file. Since there is a limit on how long logs are retained, there are no concerns about this ever starting to take longer.

I chose this method over adding parsing functionality into the script out of convenience. Using the script would require additional logic and either hardcoding locations to check for logs or dealing with more arguments. As it is designed, anyone can easily plugin a list of passwords without having to worry about many command line options or editing the script.

Results

The script accurately provides information on passwords that HaveIBeenPwned has not seen in prior breaches. While there were more unseen passwords than one may expect (1,196 or ~7.4% of all unique passwords as of writing), it provides interesting insight into what some actors may be targeting. The results also reveal patterns for password mutations that are being leveraged for access attempts:

| deploy12345 deploy123456 deploy1234567 deploy12345678 deploy@2022 deploy@2023 deploy@2025 deploy2025 deploy@321 deploypass P@$$vords123 P@$sw0rd# P4$$word!@# P455wORd |

P@55W0RD2004 Pa$$word2016! pa33w0rd!@ Pa55w0rd@2021 passw0rd!@#$ pass@w0rd.12345 passwd@123! PaSswORD@123 password@2!@ PaSswORd2021 password!2024 password!2025 Password43213 password!@#456 |

Password Patterns & Analysis

Analyzing the passwords seen in the above Results section can provide some insight into what techniques are being used to generate passwords.

Consider the above sample of results. Broadly speaking, this ‘deploy family’ of passwords was likely generated by starting with a base password of “deploy” and adding common modifiers to increase complexity. Seen here are good examples of the most simple ones: adding the year (with an @ sign in this case) and adding sequential numbers.

The rest of the entries above are all based on the word ‘password’. These are more complex than what we saw with ‘deploy’. Below are three entries, a plain explanation of a Hashcat rule that could be used to come up with it, and a sample implementation of the rule:

P4$$word!@#- Capitalize the first letter, replace

a’s with4’s, replaces’s with$’s, add!@#to end –c sa4 ss$ $! $@ $#

- Capitalize the first letter, replace

P@55W0RD2004- Capitalize all letters, replace

a’s with@’s, replaces’s with5’s, replaceo’s with 0’s, and add a year to the end –u sa@ ss5 so0 $2 $0 $0 $4

- Capitalize all letters, replace

Password!2024- Capitalize the first letter, add

!and a year to the end –t0 $! $2 $0 $2 $4

- Capitalize the first letter, add

Both Hashcat and John the Ripper can make these modifications by using rules to augment password lists. The rules allow various changes to input such as replacing or swapping certain characters with others. Note that while much of the rules syntax between these tools is similar, there are some differences [5].

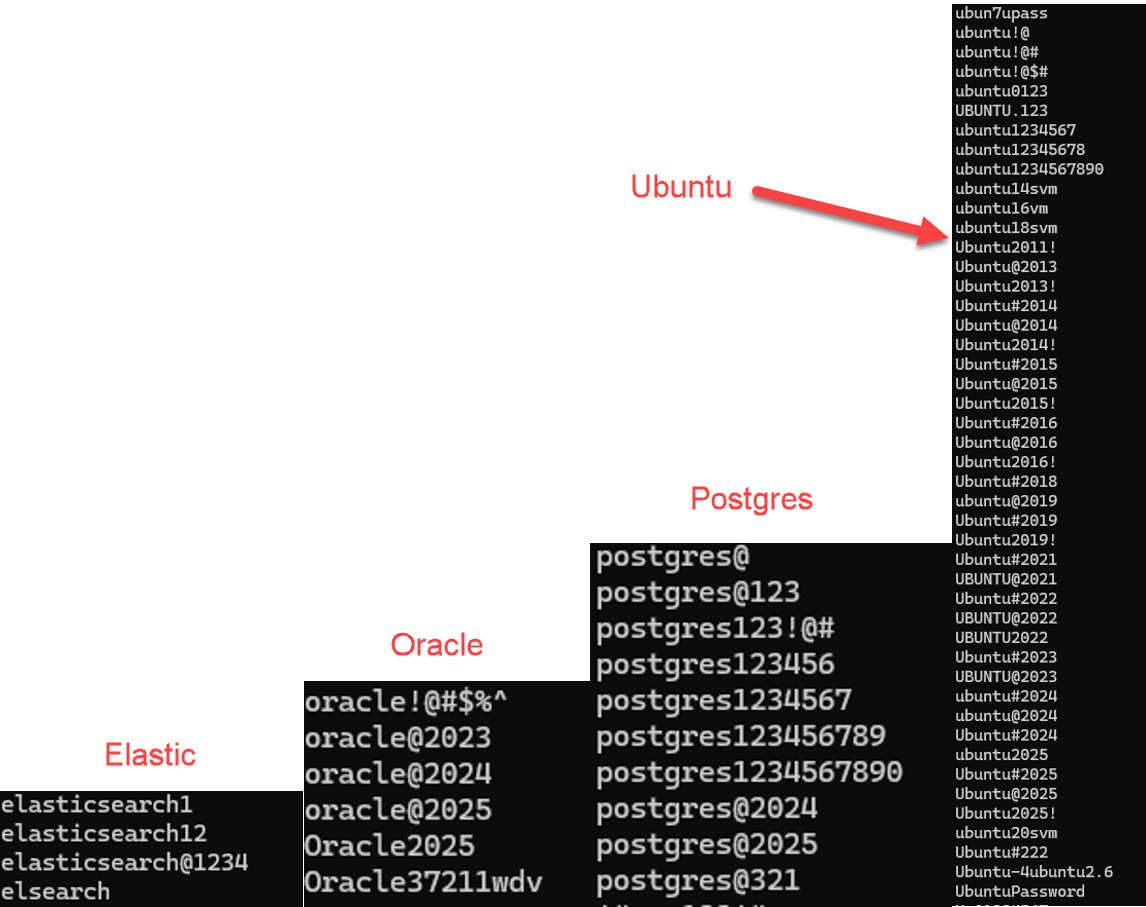

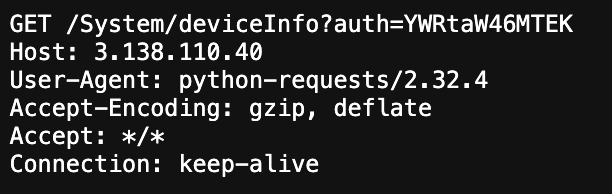

Looking through the unseen passwords, we can also see more specific targets such as Elasticsearch, Oracle, PostgresSQL, and Ubuntu. Figure 5 shows some of these passwords, which use the same kind of modifications mentioned earlier, and illustrate the relative difference in frequency.

Figure 5: Passwords related to specific services/platforms.

Overall Takeaway

While a good amount of manual analysis will still be required, these results can provide a lot of value and the script helps cut down on time. We can learn more about common password modifications to avoid and even get an idea of the relative interest of different targets. In Figure 5 alone, we can see that PostgresSQL may be roughly two times more likely to be targeted than Elasticsearch with newer installations being targeted in particular.

For future work, I would add a feature to recheck the known unseen passwords to identify if they happen to be newly breached.

Additionally, I may consider adding two features for convenience. The first would be re-sorting the unseen file since it is append only. The second would be parsing features to simplify automation and allow the script to provide more functionality for end users.

[1] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

[2] https://haveibeenpwned.com/API/v3#PwnedPasswords

[3] https://github.com/MeepStryker/queryHIBP

[4] https://haveibeenpwned.com/API/v3#UserAgent

[5] https://hashcat.net/wiki/doku.php?id=rule_based_attack#compatibility_with_other_rule_engines

—

Jesse La Grew

Handler

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

![[Guest Diary] Distracting the Analyst for Fun and Profit, (Tue, Sep 23rd)](https://www.ironcastle.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/status-8.gif)