Original release date: November 17, 2022

Summary

Actions to Take Today to Mitigate Cyber Threats from Ransomware:

• Prioritize remediating known exploited vulnerabilities.

• Enable and enforce multifactor authentication with strong passwords

• Close unused ports and remove any application not deemed necessary for day-to-day operations.

Note: This joint Cybersecurity Advisory (CSA) is part of an ongoing #StopRansomware effort to publish advisories for network defenders that detail various ransomware variants and ransomware threat actors. These #StopRansomware advisories include recently and historically observed tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and indicators of compromise (IOCs) to help organizations protect against ransomware. Visit stopransomware.gov to see all #StopRansomware advisories and to learn more about other ransomware threats and no-cost resources.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) are releasing this joint CSA to disseminate known Hive IOCs and TTPs identified through FBI investigations as recently as November 2022.

FBI, CISA, and HHS encourage organizations to implement the recommendations in the Mitigations section of this CSA to reduce the likelihood and impact of ransomware incidents. Victims of ransomware operations should report the incident to their local FBI field office or CISA.

Download the PDF version of this report: pdf, 852.9 kb.

Technical Details

Note: This advisory uses the MITRE ATT&CK® for Enterprise framework, version 12. See MITRE ATT&CK for Enterprise for all referenced tactics and techniques.

As of November 2022, Hive ransomware actors have victimized over 1,300 companies worldwide, receiving approximately US$100 million in ransom payments, according to FBI information. Hive ransomware follows the ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) model in which developers create, maintain, and update the malware, and affiliates conduct the ransomware attacks. From June 2021 through at least November 2022, threat actors have used Hive ransomware to target a wide range of businesses and critical infrastructure sectors, including Government Facilities, Communications, Critical Manufacturing, Information Technology, and especially Healthcare and Public Health (HPH).

The method of initial intrusion will depend on which affiliate targets the network. Hive actors have gained initial access to victim networks by using single factor logins via Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP), virtual private networks (VPNs), and other remote network connection protocols [T1133]. In some cases, Hive actors have bypassed multifactor authentication (MFA) and gained access to FortiOS servers by exploiting Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) CVE-2020-12812. This vulnerability enables a malicious cyber actor to log in without a prompt for the user’s second authentication factor (FortiToken) when the actor changes the case of the username.

Hive actors have also gained initial access to victim networks by distributing phishing emails with malicious attachments [T1566.001] and by exploiting the following vulnerabilities against Microsoft Exchange servers [T1190]:

- CVE-2021-31207 – Microsoft Exchange Server Security Feature Bypass Vulnerability

- CVE-2021-34473 – Microsoft Exchange Server Remote Code Execution Vulnerability

- CVE-2021-34523 – Microsoft Exchange Server Privilege Escalation Vulnerability

After gaining access, Hive ransomware attempts to evade detention by executing processes to:

- Identify processes related to backups, antivirus/anti-spyware, and file copying and then terminating those processes to facilitate file encryption [T1562].

- Stop the volume shadow copy services and remove all existing shadow copies via vssadmin on command line or via PowerShell [T1059] [T1490].

- Delete Windows event logs, specifically the System, Security and Application logs [T1070].

Prior to encryption, Hive ransomware removes virus definitions and disables all portions of Windows Defender and other common antivirus programs in the system registry [T1112].

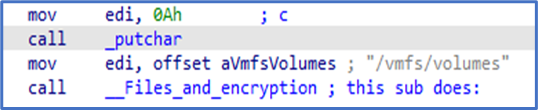

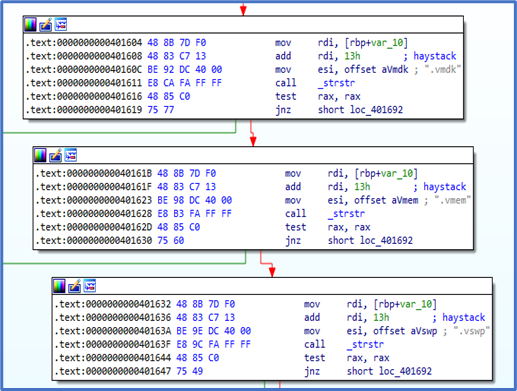

Hive actors exfiltrate data likely using a combination of Rclone and the cloud storage service Mega.nz [T1537]. In addition to its capabilities against the Microsoft Windows operating system, Hive ransomware has known variants for Linux, VMware ESXi, and FreeBSD.

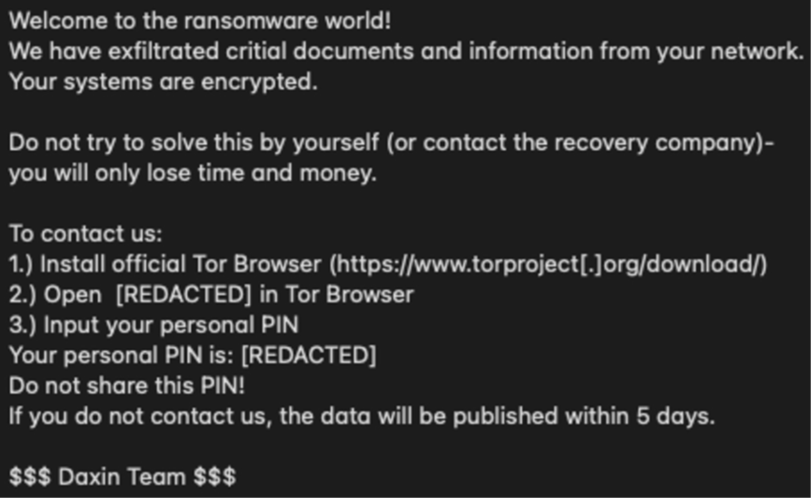

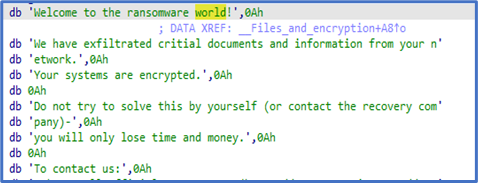

During the encryption process, a file named *.key (previously *.key.*) is created in the root directory (C: or /root/). Required for decryption, this key file only exists on the machine where it was created and cannot be reproduced. The ransom note, HOW_TO_DECRYPT.txt is dropped into each affected directory and states the *.key file cannot be modified, renamed, or deleted, otherwise the encrypted files cannot be recovered [T1486]. The ransom note contains a “sales department” .onion link accessible through a TOR browser, enabling victim organizations to contact the actors through a live chat panel to discuss payment for their files. However, some victims reported receiving phone calls or emails from Hive actors directly to discuss payment.

The ransom note also threatens victims that a public disclosure or leak site accessible on the TOR site, “HiveLeaks”, contains data exfiltrated from victim organizations who do not pay the ransom demand (see figure 1 below). Additionally, Hive actors have used anonymous file sharing sites to disclose exfiltrated data (see table 1 below).

|

https://mega[.]nz |

|

https://send.exploit[.]in |

|

https://ufile[.]io |

|

https://www.sendspace[.]com |

|

https://privatlab[.]net |

|

https://privatlab[.]com |

Once the victim organization contacts Hive actors on the live chat panel, Hive actors communicate the ransom amount and the payment deadline. Hive actors negotiate ransom demands in U.S. dollars, with initial amounts ranging from several thousand to millions of dollars. Hive actors demand payment in Bitcoin.

Hive actors have been known to reinfect—with either Hive ransomware or another ransomware variant—the networks of victim organizations who have restored their network without making a ransom payment.

Indicators of Compromise

Threat actors have leveraged the following IOCs during Hive ransomware compromises. Note: Some of these indicators are legitimate applications that Hive threat actors used to aid in further malicious exploitation. FBI, CISA, and HHS recommend removing any application not deemed necessary for day-to-day operations. See tables 2–3 below for IOCs obtained from FBI threat response investigations as recently as November 2022.

|

Known IOCs – Files |

|

HOW_TO_DECRYPT.txt typically in directories with encrypted files |

|

*.key typically in the root directory, i.e., C: or /root |

|

hive.bat |

|

shadow.bat |

|

asq.r77vh0[.]pw – Server hosted malicious HTA file |

|

asq.d6shiiwz[.]pw – Server referenced in malicious regsvr32 execution |

|

asq.swhw71un[.]pw – Server hosted malicious HTA file |

|

asd.s7610rir[.]pw – Server hosted malicious HTA file |

|

Windows_x64_encrypt.dll |

|

Windows_x64_encrypt.exe |

|

Windows_x32_encrypt.dll |

|

Windows_x32_encrypt.exe |

|

Linux_encrypt |

|

Esxi_encrypt |

|

Known IOCs – Events |

|

System, Security and Application Windows event logs wiped |

|

Microsoft Windows Defender AntiSpyware Protection disabled |

|

Microsoft Windows Defender AntiVirus Protection disabled |

|

Volume shadow copies deleted |

|

Normal boot process prevented |

|

Known IOCs – Logged Processes |

|

wevtutil.exe cl system |

|

wevtutil.exe cl security |

|

wevtutil.exe cl application |

|

vssadmin.exe delete shadows /all /quiet |

|

wmic.exe SHADOWCOPY /nointeractive |

|

wmic.exe shadowcopy delete |

|

bcdedit.exe /set {default} bootstatuspolicy ignoreallfailures |

|

bcdedit.exe /set {default} recoveryenabled no |

|

84.32.188[.]57 |

84.32.188[.]238 |

|

93.115.26[.]251 |

185.8.105[.]67 |

|

181.231.81[.]239 |

185.8.105[.]112 |

|

186.111.136[.]37 |

192.53.123[.]202 |

|

158.69.36[.]149 |

46.166.161[.]123 |

|

108.62.118[.]190 |

46.166.161[.]93 |

|

185.247.71[.]106 |

46.166.162[.]125 |

|

5.61.37[.]207 |

46.166.162[.]96 |

|

185.8.105[.]103 |

46.166.169[.]34 |

|

5.199.162[.]220 |

93.115.25[.]139 |

|

5.199.162[.]229 |

93.115.27[.]148 |

|

89.147.109[.]208 |

83.97.20[.]81 |

|

5.61.37[.]207 |

5.199.162[.]220 |

|

5.199.162[.]229; |

46.166.161[.]93 |

|

46.166.161[.]123; |

46.166.162[.]96 |

|

46.166.162[.]125 |

46.166.169[.]34 |

|

83.97.20[.]81 |

84.32.188[.]238 |

|

84.32.188[.]57 |

89.147.109[.]208 |

|

93.115.25[.]139; |

93.115.26[.]251 |

|

93.115.27[.]148 |

108.62.118[.]190 |

|

158.69.36[.]149/span> |

181.231.81[.]239 |

|

185.8.105[.]67 |

185.8.105[.]103 |

|

185.8.105[.]112 |

185.247.71[.]106 |

|

186.111.136[.]37 |

192.53.123[.]202 |

MITRE ATT&CK TECHNIQUES

See table 4 for all referenced threat actor tactics and techniques listed in this advisory.

|

Initial Access |

||

|

Technique Title |

ID |

Use |

|

External Remote Services |

Hive actors gain access to victim networks by using single factor logins via RDP, VPN, and other remote network connection protocols. |

|

|

Exploit Public-Facing Application |

Hive actors gain access to victim network by exploiting the following Microsoft Exchange vulnerabilities: CVE-2021-34473, CVE-2021-34523, CVE-2021-31207, CVE-2021-42321. |

|

|

Phishing |

Hive actors gain access to victim networks by distributing phishing emails with malicious attachments. |

|

|

Execution |

||

|

Technique Title |

ID |

Use |

|

Command and Scripting Interpreter |

Hive actors looks to stop the volume shadow copy services and remove all existing shadow copies via vssadmin on command line or PowerShell. |

|

|

Defense Evasion |

||

|

Technique Title |

ID |

Use |

|

Indicator Removal on Host |

Hive actors delete Windows event logs, specifically, the System, Security and Application logs. |

|

|

Modify Registry |

Hive actors set registry values for DisableAntiSpyware and DisableAntiVirus to 1. |

|

|

Impair Defenses |

Hive actors seek processes related to backups, antivirus/anti-spyware, and file copying and terminates those processes to facilitate file encryption. |

|

|

Exfiltration |

||

|

Technique Title |

ID |

Use |

|

Transfer Data to Cloud Account |

Hive actors exfiltrate data from victims, using a possible combination of Rclone and the cloud storage service Mega.nz. |

|

|

Impact |

||

|

Technique Title |

|

Use |

|

Data Encrypted for Impact |

Hive actors deploy a ransom note HOW_TO_DECRYPT.txt into each affected directory which states the *.key file cannot be modified, renamed, or deleted, otherwise the encrypted files cannot be recovered. |

|

|

Inhibit System Recovery |

Hive actors looks to stop the volume shadow copy services and remove all existing shadow copies via vssadmin via command line or PowerShell. |

|

Mitigations

FBI, CISA, and HHS recommend organizations, particularly in the HPH sector, implement the following to limit potential adversarial use of common system and network discovery techniques and to reduce the risk of compromise by Hive ransomware:

- Verify Hive actors no longer have access to the network.

- Install updates for operating systems, software, and firmware as soon as they are released. Prioritize patching VPN servers, remote access software, virtual machine software, and known exploited vulnerabilities. Consider leveraging a centralized patch management system to automate and expedite the process.

- Require phishing-resistant MFA for as many services as possible—particularly for webmail, VPNs, accounts that access critical systems, and privileged accounts that manage backups.

- If used, secure and monitor RDP.

- Limit access to resources over internal networks, especially by restricting RDP and using virtual desktop infrastructure.

- After assessing risks, if you deem RDP operationally necessary, restrict the originating sources and require MFA to mitigate credential theft and reuse.

- If RDP must be available externally, use a VPN, virtual desktop infrastructure, or other means to authenticate and secure the connection before allowing RDP to connect to internal devices.

- Monitor remote access/RDP logs, enforce account lockouts after a specified number of attempts to block brute force campaigns, log RDP login attempts, and disable unused remote access/RDP ports.

- Be sure to properly configure devices and enable security features.

- Disable ports and protocols not used for business purposes, such as RDP Port 3389/TCP.

- Maintain offline backups of data, and regularly maintain backup and restoration. By instituting this practice, the organization ensures they will not be severely interrupted, and/or only have irretrievable data.

- Ensure all backup data is encrypted, immutable (i.e., cannot be altered or deleted), and covers the entire organization’s data infrastructure. Ensure your backup data is not already infected.,

- Monitor cyber threat reporting regarding the publication of compromised VPN login credentials and change passwords/settings if applicable.

- Install and regularly update anti-virus or anti-malware software on all hosts.

- Enable PowerShell Logging including module logging, script block logging and transcription.

- Install an enhanced monitoring tool such as Sysmon from Microsoft for increased logging.

- Review the following additional resources.

- The joint advisory from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States on Technical Approaches to Uncovering and Remediating Malicious Activity provides additional guidance when hunting or investigating a network and common mistakes to avoid in incident handling.

- The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency-Multi-State Information Sharing & Analysis Center Joint Ransomware Guide covers additional best practices and ways to prevent, protect, and respond to a ransomware attack.

- StopRansomware.gov is the U.S. Government’s official one-stop location for resources to tackle ransomware more effectively.

If your organization is impacted by a ransomware incident, FBI, CISA, and HHS recommend the following actions.

- Isolate the infected system. Remove the infected system from all networks, and disable the computer’s wireless, Bluetooth, and any other potential networking capabilities. Ensure all shared and networked drives are disconnected.

- Turn off other computers and devices. Power-off and segregate (i.e., remove from the network) the infected computer(s). Power-off and segregate any other computers or devices that share a network with the infected computer(s) that have not been fully encrypted by ransomware. If possible, collect and secure all infected and potentially infected computers and devices in a central location, making sure to clearly label any computers that have been encrypted. Powering-off and segregating infected computers and computers that have not been fully encrypted may allow for the recovery of partially encrypted files by specialists.

- Secure your backups. Ensure that your backup data is offline and secure. If possible, scan your backup data with an antivirus program to check that it is free of malware.

In addition, FBI, CISA, and HHS urge all organizations to apply the following recommendations to prepare for, mitigate/prevent, and respond to ransomware incidents.

Preparing for Cyber Incidents

- Review the security posture of third-party vendors and those interconnected with your organization. Ensure all connections between third-party vendors and outside software or hardware are monitored and reviewed for suspicious activity.

- Implement listing policies for applications and remote access that only allow systems to execute known and permitted programs under an established security policy.

- Document and monitor external remote connections. Organizations should document approved solutions for remote management and maintenance, and immediately investigate if an unapproved solution is installed on a workstation.

- Implement a recovery plan to maintain and retain multiple copies of sensitive or proprietary data and servers in a physically separate, segmented, and secure location (i.e., hard drive, storage device, the cloud).

Identity and Access Management

- Require all accounts with password logins (e.g., service account, admin accounts, and domain admin accounts) to comply with National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standards for developing and managing password policies.

- Use longer passwords consisting of at least 8 characters and no more than 64 characters in length.

- Store passwords in hashed format using industry-recognized password managers.

- Add password user “salts” to shared login credentials.

- Avoid reusing passwords.

- Implement multiple failed login attempt account lockouts.

- Disable password “hints.”

- Refrain from requiring password changes more frequently than once per year unless a password is known or suspected to be compromised.

Note: NIST guidance suggests favoring longer passwords instead of requiring regular and frequent password resets. Frequent password resets are more likely to result in users developing password “patterns” cyber criminals can easily decipher. - Require administrator credentials to install software.

- Require phishing-resistant multifactor authentication for all services to the extent possible, particularly for webmail, virtual private networks, and accounts that access critical systems.

- Review domain controllers, servers, workstations, and active directories for new and/or unrecognized accounts.

- Audit user accounts with administrative privileges and configure access controls according to the principle of least privilege.

- Implement time-based access for accounts set at the admin level and higher. For example, the Just-in-Time (JIT) access method provisions privileged access when needed and can support enforcement of the principle of least privilege (as well as the Zero Trust model). This is a process where a network-wide policy is set in place to automatically disable admin accounts at the Active Directory level when the account is not in direct need. Individual users may submit their requests through an automated process that grants them access to a specified system for a set timeframe when they need to support the completion of a certain task.

Protective Controls and Architecture

- Segment networks to prevent the spread of ransomware. Network segmentation can help prevent the spread of ransomware by controlling traffic flows between—and access to—various subnetworks and by restricting adversary lateral movement.

- Identify, detect, and investigate abnormal activity and potential traversal of the indicated ransomware with a networking monitoring tool. To aid in detecting the ransomware, implement a tool that logs and reports all network traffic, including lateral movement activity on a network. Endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools are particularly useful for detecting lateral connections as they have insight into common and uncommon network connections for each host.

- Install, regularly update, and enable real time detection for antivirus software on all hosts.

Vulnerability and Configuration Management

- Consider adding an email banner to emails received from outside your organization.

- Disable command-line and scripting activities and permissions. Privilege escalation and lateral movement often depend on software utilities running from the command line. If threat actors are not able to run these tools, they will have difficulty escalating privileges and/or moving laterally.

- Ensure devices are properly configured and that security features are enabled.

- Restrict Server Message Block (SMB) Protocol within the network to only access necessary servers and remove or disable outdated versions of SMB (i.e., SMB version 1). Threat actors use SMB to propagate malware across organizations.

REFERENCES

- Stopransomware.gov is a whole-of-government approach that gives one central location for ransomware resources and alerts.

- Resource to mitigate a ransomware attack: CISA-Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS-ISAC) Joint Ransomware Guide.

- No-cost cyber hygiene services: Cyber Hygiene Services and Ransomware Readiness Assessment.

INFORMATION REQUESTED

The FBI, CISA, and HHS do not encourage paying a ransom to criminal actors. Paying a ransom may embolden adversaries to target additional organizations, encourage other criminal actors to engage in the distribution of ransomware, and/or fund illicit activities. Paying the ransom also does not guarantee that a victim’s files will be recovered. However, the FBI, CISA, and HHS understand that when businesses are faced with an inability to function, executives will evaluate all options to protect their shareholders, employees, and customers. Regardless of whether you or your organization decide to pay the ransom, the FBI, CISA, and HHS urge you to promptly report ransomware incidents to your local FBI field office, or to CISA at report@cisa.gov or (888) 282-0870. Doing so provides investigators with the critical information they need to track ransomware attackers, hold them accountable under US law, and prevent future attacks.

The FBI may seek the following information that you determine you can legally share, including:

- Recovered executable files

- Live random access memory (RAM) capture

- Images of infected systems

- Malware samples

- IP addresses identified as malicious or suspicious

- Email addresses of the attackers

- A copy of the ransom note

- Ransom amount

- Bitcoin wallets used by the attackers

- Bitcoin wallets used to pay the ransom

- Post-incident forensic reports

DISCLAIMER

The information in this report is being provided “as is” for informational purposes only. FBI, CISA, and HHS do not endorse any commercial product or service, including any subjects of analysis. Any reference to specific commercial products, processes, or services by service mark, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by FBI, CISA, or HHS.

Revisions

- Initial Version: November 17, 2022

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.